Unlike most sociologists, I am not a man of the Left. Moreover, I have little respect for most of what passes as sociology today. But Durkheim was still right—it is the queen of the social sciences (properly executed).

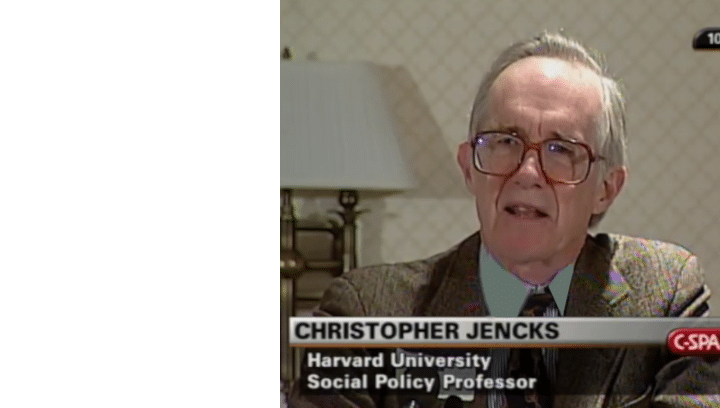

We just lost one of the titans of American sociology, Christopher Jencks. The Harvard sociologist was not a conservative; indeed, he was a socialist and an egalitarian. But what made him special is that he was an honest scholar, one who drew his conclusions based on the data. Sadly, that makes him unique.

Jencks died on February 8 of complications traced to Alzheimer’s disease. His 1972 book, Inequality: A Reassessment of the Effect of Family and Schooling in America, broke new ground: he challenged the conventional wisdom on the effects that nature and nurture have on generating inequality.

Jencks, found, as did sociologist James S. Coleman before him, that what happens in the home is more important in affecting academic achievement than what happens in the school. This is not what an egalitarian wants to hear: it showed that public policy could only do so much to decrease inequality. But he did not allow his ideological predilections to conquer.

He studied people with identical IQs who were raised in similar families with nearly identical educational and social backgrounds. He found that some did well economically and others did not. Taking into consideration both hereditary and social factors, he could explain roughly one-quarter of the reasons why some were “winners” and others were “losers.” So what mattered most? Luck. This residual category—it accounts for 75 percent of all the variables—was a matter of timing, chance, and other anomalies. He called it luck.

It is important to note that Jencks never suggested that luck was more important than virtue and a strong work ethic. His point was that there is as much inequality within families as there is in society.

This should make sense to everyone. The typical family is one where some siblings do well and others do not. Yet they come from the same parents and are raised in the same household. In other words, nature and nurture are similar yet the outcomes are quite different. Being at the right place at the right time, making important connections, maturing at a late age—there are all kinds of reasons why some family members excel and others do not.

If luck accounts for the lion’s share of what makes for success, there is little that public policy can do to ameliorate inequality. This is not a plea to do nothing: it is simply a frank admission of the limits of education and social engineering.

What Jencks found needs to be heeded by today’s social scientists, educators, administrators and government officials. Too often they think they can treat human beings as if they were silly putty—shaping and reshaping our milieu to yield equality. Not only does this have little effect, it typically tramples on our dignity and freedom.

Christians understand that humans are not toys to be played with by the ruling class. Jencks found good social science reasons not to even try.