Catholic League president Bill Donohue comments on Lent:

Those who observe Lent are not known as cultural radicals, yet they clearly qualify as such.

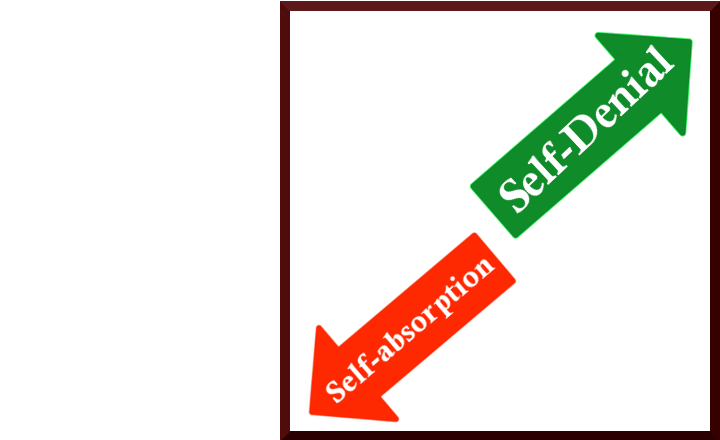

Repenting for our sins is common practice for Catholics during Lent, though it is not understood—may even be the object of scorn—by secularists. Many of them do not believe in the existence of sin, never mind making reparations for it. Even more countercultural is the Lenten practice of self-denial.

In a society marked by self-absorption, nothing could be more extreme than self-denial. The idea that we should deny ourselves what we want rings hollow with narcissists, many of whom are secularists. They are the true children of Humanist Psychology.

Abraham Maslow posited that we all have needs, some of which are basic, such as food and water and feeling safe. At the top of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is self-actualization, the idea that we owe it to ourselves to be self-fulfilled.

Not surprisingly, his work was celebrated in the 1960s and 1970s, the two most culturally corrupt decades in American history. It was in the 1970s that Tom Wolfe coined the phrase the “Me Society,” and Christopher Lasch wrote The Culture of Narcissism.

Carl Rogers, another humanist psychologist at this time, wrote that self-actualization means we are all arbiters of our own truth, and only by acting on our feelings can we be truly human. He argued that rebellion against traditional moral norms, as found in Christianity, was good for the individual and society.

Maslow and Rogers helped destroy people’s lives. In fact, Rogers destroyed an entire order of nuns in Los Angeles, the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary. The naive nuns followed his advice by questioning the norms and values they had committed themselves to, and wound up totally deracinated.

Maslow and Rogers got it all wrong. They never understood the Lenten precept that self-denial can be liberating. By giving of ourselves to Jesus, and to others, we experience real self-actualization, not the one steeped in self-absorption. Selflessness has its own rewards.

Selflessness also pays significant social dividends. Mother Teresa could not have comforted so many of the sick and dying had it not been for her selflessness. Had she been self-absorbed, no one would have benefited from her care. There are many other persons who have also yielded great social dividends by sacrificing for others, though they are not publicly known.

Who were the men and women who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust? They were not secularists—they were people of faith.

Samuel P. Oliner, and his wife, Pearl M. Oliner, are the authors of The Altruistic Personality, a book about who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust. These two non-believing Jewish sociologists interviewed nearly seven hundred persons, comprising rescuers, nonrescuers, and survivors in several countries in Nazi-occupied Europe.

They found there was a significant difference between rescuers and nonrescuers when it came to accepting “the importance of responsibility in maintaining their attachments to people.” They learned that “More rescuers were willing to give more than what they might necessarily receive in return.”

Catholics and Protestants who were imbued with their faith were the most likely to rescue Jews. Pearl Oliner explained why Catholics had the best record. They were “significantly marked by a Sharing disposition.” In short, these Catholics embodied the “altruistic personality.”

Who were the least likely to rescue Jews? The self-absorbed. The Oliners concluded that “self-preoccupation,” or the tendency to focus on oneself, not others, was the principal reason why they failed to act. “In recalling the values learned from their parents, rescuers emphasized values relating to self significantly less frequently than nonrescuers.” It was the “free spirits,” the self-actualization types, who balked when it came to helping Jews.

Regrettably, our society is more self-absorbed now than ever before.

Lent is delightfully different. It signals an awareness that there is much more to this world than “me,” and that self-giving is a national treasure, not simply a personal attribute. We need more Lenten cultural radicals, not less of them.