|

By Robert P. Lockwood |

|

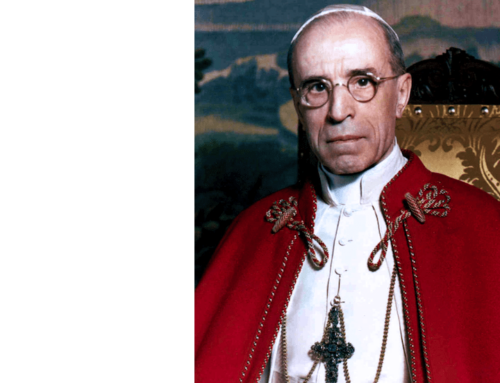

(March 2000) Pope John Paul II recently issued a half-hearted apology for Catholics’ failure to oppose the torture and killing of six million Jews during the horrible Holocaust, but at the same time he tried to excuse Pius XII, the pope at the time, for his silence and collaboration.” – Dr. Al Snyder writing in Thea Times Examiner, Greenville, North Carolina, March 16, 2000 The failure to utter a candid word about the Final Solution in progress proclaimed to the world that the Vicar of Christ was not moved to pity and anger. From this point of view he was the ideal Pope for Hitler’s unspeakable plan. He was Hitler’s pawn. He was Hitler’s Pope.” – John Cornwell, Hitler’s Pope (Viking Press, 1999) For nearly 20 years after World War II, Pope Pius XII (1939-1958) was honored by the world for his actions in saving countless Jewish lives in the face of the Nazi Holocaust. His death on October 9, 1958 brought a moment of silence from Leonard Bernstein while he conducted at New York’s Carnegie Hall.1 Golda Meir, future Israeli Prime Minister and then Israeli representative to the United Nations, spoke on the floor of the General Assembly: “During the ten years of Nazi terror, when our people went through the horrors of martyrdom, the Pope raised his voice to condemn the persecutors and commiserate with the victims.”2 In his book Hitler, the War and the Pope (Genesis Press, August 2000), author Ronald Rychlak provides a sampling of some of the Jewish organizations that praised Pope Pius XII at the time of his death for saving Jewish lives during the horror of the Nazi Holocaust: the World Jewish Congress, the Anti-Defamation League, the Synagogue Council of America, the Rabbinical Council of America, the American Jewish Congress, the New York Board of Rabbis, the American Jewish Committee, the Central Conference of American Rabbis, the American Jewish Committee, the Central Conference of American Rabbis, the National Conference of Christians and Jews and the National Council of Jewish Women. Yet, over 40 years after the death of Pius XII, he is condemned for his “shameful silence”3 in the face of the Holocaust. He is commonly accused of not only silence, but actual complicity in the Holocaust, as charged by Dr. Snyder above, and called “Hitler’s Pope” in a best-selling book released by a major American publisher. When critics are reminded of the universal praise he received from Jewish organizations in life and death, such praise is dismissed as merely “political” statements, as if those Jews who had lived through the Holocaust would insult the memory of the millions killed for some ephemeral political gain. Reading commentaries and news reports in the new Millennium, it may seem that the Church under Pius XII was as responsible for the Holocaust as the Nazis who carried it out. In reporting and editorials on the Holocaust, it is routinely presented as historical fact that Pius XII and the Church were, at best, stonily silent, or, at worst, aided and abetted the Nazi killing machine. Many Catholics in America simply accept these contemporary charges, and are silent at the mere mention of Pius XII. The historical reality of the pontificate of Pius XII has nearly been lost in the face of the strident campaign against him. Nearly lost as well has been the reality of how contemporaries – friends and enemies – viewed his papacy and actions during World War II and the depth and breadth of Catholic action in response to the Holocaust. Anti-Catholicism thrives on invented history that becomes part of the accepted cultural corpus. The corruption and nadir of the faith prior to the Reformation, the “black legend” of the Spanish in the New World, papal promotion of the slave trade, the purely sectarian nature of the Inquisition, the Church as anti-science as evidenced in the Galileo affair, unendingly scandalous papal lives: our understanding of so much of history has been colored by a campaign meant to influence the outcome of theological and political disputes between Protestants and Catholics in the 19th century. America was highly influenced by the post-Reformation British propaganda meant to create a myth of an evil Catholicism out to destroy free and Protestant England. Legends of the evil-doing of the pope and his minions established in Western thinking an assumption of anti-Catholicism as not only normative for right-thinking people, but correct and historically valid.4 Conventional wisdom is more often the creation of propaganda than fact. The purpose here is not to supply a definitive biographical treatment of Pope Pius XII, nor review the complicated political environment of Europe from World War I through the pontiff’s death. Additionally, the impact on the life of the Church of the pontiff who was the “father of Vatican II” awaits a more detailed biography. Here we will confine ourselves to an understanding of the roots of the accusations against Pius, and review his career and wartime pontificate in light of the horror of the Holocaust.

The Creation of Conventional Wisdom It is becoming more evident where the conventional wisdom lies in regard to Pope Pius XII. When Pope John Paul II issued his historic apology for mistakes and errors in Christian history, he was savaged by pundits and news reports for his “silence” in regard to the “silence” of Pope Pius XII.5 Lance Morrow in Time magazine, referred to the Church’s “terrible inaction and silence in the face of the Holocaust” and described any defense of Pius or the Church as “moral pettifogging.”6 He made such statements without the need for substantiation because the charges against Pius XII are simply accepted as “fact” and any disagreement becomes on a par with those who deny the reality of the Holocaust itself. Routine accusations against the Church in World War II dominated coverage of the pope’s Lenten Millennial pilgrimage to the Holy Land. The television show “60 Minutes” just prior to the papal trip ran a detailed propaganda piece accusing Pius XII not only of silence during the Holocaust, but virtual complicity that stemmed from personal anti-Semitism and the desire to expand papal power. Contemporary Catholics are witnessing the creation of a myth in regard to Pius XII, a propaganda campaign as relentless as any created by 19th century anti-Catholic apologists. The view of Pius XII as Nazi collaborator did not begin as a case study of historical revisionism. It did not even begin within historical studies themselves or from available historical documentation, including transcripts of the Nuremberg trials, or government records made public. The myth of Pius XII began in earnest in 1963 in a drama created for the stage by Rolf Hochhuth, an otherwise obscure German playwright born in 1931. Hochhuth was part of a post-World War II trend in theatre called “Documentary Theatre” or “Theatre of Fact.” The trend grew out of an American form of theatre popularized during the Depression. The point was to adapt social issues to theatrical presentation by utilizing factual reports or documentation. The “facts” would be more important than artistic presentation. Documentation and transcripts would provide the script for the play. It was seen in more recent times with Vietnam war morality plays based on the Pentagon Papers, or presentations whose dialogue is directly culled from the White House tapes of Richard Nixon. In post-war Germany, Hochhuth and others employed the “Theatre of Fact” as a means to explore and expose Nazi history. Peter Weiss’s “The Investigation,” for example, used excerpts from testimony provided from officials of the Auschwitz death camp. Hochhuth, however, created a more traditional theatrical presentation, though it was presented in the style of “Theatre of Fact.” Turgid in length, in 1963’s Der Stellvertreter (The Representativeor The Deputy) Hochhuth charged through a fictional presentation that Pius XII maintained an icy, cynical and uncaring silence during the Holocaust. More interested in Vatican investments than human lives, Pius was presented as a cigarette-smoking dandy with Nazi leanings. (Hochhuth also authored a play charging the complicity of Winston Churchill in a murder. No one paid much attention to that effort.) The Deputy, even to Pius’ most strenuous detractors, is readily dismissed. John Cornwell in Hitler’s Pope describes Der Stellvertreter as “historical fiction based on scant documentation…(T)he characterization of Pacelli (Pius XII) as a money-grubbing hypocrite is so wide of the mark as to be ludicrous. Importantly, however, Hochhuth’s play offends the most basic criteria of documentary: that such stories and portrayals are valid only if they are demonstrably true.”7 Yet The Deputy, despite its evident flaws, prejudices and lack of historicity, laid the foundation for the charges against Pius XII, five years after his death. There was fertile ground. Pius XII was unpopular with certain schools of post World War II historians for the anti-Stalinist, anti-Communist agenda of his later pontificate. This was a period where leftist sentiments in the West were still tied to a flirtation with Stalinism, though Soviet Premier Nikita Kruschev’s opening up to the world of the true Stalin legacy would slowly erode such views. In the heady atmosphere of leftist academic circles, particularly in Italy in the late 1950s and throughout the 1960s, the general charge against Pius was that while he was not pro-Nazi during the war, he hated Bolshevism more than he hated Hitler. For the most part, this was based on the pope’s opposition to the Allied demand for unconditional German surrender. He believed such a condition would only continue the horror of the war and increase the killing. That stand was later interpreted as a desire on the pontiff’s part to maintain a strong Germany as a bulwark against communism. The pope was also blamed for helping to create the anti-Soviet atmosphere that resulted in the “Cold War” in the late 1940s and 1950s. Hochhuth’s charge of papal “silence” fit the theory that Pius refused to publicly criticize Germany in order that the country could serve effectively as an ongoing block to Soviet expansion. The theory, of course, was as much fiction as Hochhuth’s play. There was no documentary evidence to even suggest such a papal strategy. But it became popular, particularly among historians with Marxist sympathies in the 1960s. Even this theory, however, did not extend to an accusation that the Pope “collaborated” in the Holocaust, nor to any charge that the Church did anything other than save hundreds of thousands of Jewish lives. The evidence was simply too clear on that saving work for refutation. However, it did provide a mercenary rationale of “politics over people” in response to the Holocaust and applied such barbarous reasoning to the pope. The Deputy, therefore, took on far greater importance than it deserved. Leftists used it as a means to discredit an anti-Communist papacy. Instead of Pius being seen as a careful and concerned pontiff working with every means available to rescue European Jews in the face of complete Nazi entrapment, an image was created of a political schemer who would sacrifice lives to stop the spread of Communism. The Deputy was merely the mouthpiece for an ideological interpretation of history that helped create the myth of a “silent” Pius XII doing nothing in the face of Nazi slaughter. There was also strong resonance within the Jewish community at the time The Deputyappeared. The Jewish world had experienced a virtual re-living of the Holocaust in the trial of Adolf Eichmann. A key figure in the Nazi Final Solution, Eichmann had been captured in Argentina in 1960, tried in Israel in 1961 and executed in 1962. For many young Jews, Eichmann’s trial was the first definitive exposure to the horror that the Nazis had implemented. At the same time, Israel was threatened on all sides by the unified Arab states. War would erupt in a very short time. The Deputy resonated with an Israel that was surrounded by enemies and would be fighting for its ultimate survival. Despite the fact, therefore, of a two-decades-old acknowledgment of papal support and assistance to the Jews during the War, Hochhuth’s unfounded charges took on all the aspects of revelation. In a column after Pope John Paul II’s apology, Uri Dormi of Jerusalem fittingly described this impact: “The Deputy appeared in Hebrew and broke the news about another silence, that of Pope Pius XII about the Holocaust. The wartime Pope, who on Christmas Eve 1941 was praised in a New York Times editorial as ‘the only ruler left on the continent of Europe who dares to raise his voice at all,’ was exposed by the young, daring dramatist.”8 It seems ludicrous that a pope praised for his actions in 1941 – and by all leading Jewish organizations throughout his life – could be discredited based on nothing more than a theatrical invention. Yet, that is what took place and has taken place since. A combination of political and social events early in the 1960s, biased historical revisionism, and an exercise in theatrical rhetoric, created the myth of the uncaring pontiff in contradiction to the clear historical record. The myth thrived because people want to believe it rather than because it was believable. Today, that myth serves its own ideological purposes. Like many of the anti-Catholic canards rooted in the culture, the myth of Pius XII is raised to attack a host of Catholic positions on issues, whether it be gay rights, a pro-abortion agenda, or even aid to parochial school parents. In Cornwell’s book, it is utilized to take sides in intramural Catholic disagreements, an obscene exploitation of the Holocaust. The myth of papal complicity in the Holocaust is certainly damaging and libelous to the memory of Pius XII. But it has also had a terribly negative impact on Catholic-Jewish relations. Beginning with the papacies of Pius XI and Pius XII, proceeding through the Vatican Council and Paul VI, great strides had been made in Catholic-Jewish relations. The papacy of John Paul II has seen one historic event after another, celebrating the Church’s understanding that all Christians are “spiritual Semites.” Yet the myth of the silence of Pius XII has overshadowed all these historic developments. It has helped to entrench a persistent anti-Catholicism within elements of the Jewish community, while creating in certain Catholic circles a deep resentment that can only be harmful for all. While nothing can fully destroy the enormous strides taken by Pope John Paul II, leaving this myth unanswered and accepted can only do great damage to what should be a deep and close relationship between Catholics and Jews, generated in part by the heroism of Pope Pius XII in saving Jewish lives during the Holocaust.

Eugenio Pacelli Eugenio Pacelli was born in Rome on March 2, 1876 to a family of 19th century Vatican lawyers. His grandfather began l’Osservatore Romano, the Vatican newspaper still published today. His father was an important financial consultant to the Vatican. Pacelli was ordained to the priesthood on Easter Sunday, 1899. He received his doctorate in Canon Law three years later, after his appointment to what would become the Vatican secretariat of state. He spent the next 15 years of his career serving a project to organize the Code of Canon Law. At the same time, he became involved with the workings of the papal diplomatic corp. By World War I he would work with the Vatican Secretary of State on maintaining contact with Church leadership on both sides in the first world war, coordinating relief work, and assisting prisoners. 9 In 1917 Pacelli was consecrated a bishop and assigned to Munich as papal representative to Bavaria. Two years later, a short-lived communist uprising in Munich would find Pacelli facing down a gun-barrel when revolutionaries invaded the nunciature. Pacelli did not back down and, when order was re-established later, refused to press charges against his assailants. As papal representative, Pacelli would witness the chaos that was post-war Germany. Serving in Munich, Pacelli was responsible for attempting to forge “concordats” between the Holy See and various German states and he carried out such agreements with Baden, Prussia and Bavaria. Concordats were treaties of agreement that spelled out the rights of the Church within a given state or country. Pacelli’s goal with such concordats – under the direction of Pope Pius XI – was to assure non-interference in the life of the Church from state authorities, and to secure traditional support for Church services in matters such as education and marital law. Hitler’s ascent began in a post-war Germany torn apart by economic, social and political strife. Based on a program involving nationalism, racial pride, socialism and anti-Semitism, Hitler took a small Bavarian racist political party in the early 1920s and rose to power in the early 1930s. In regard to Hitler or the Nazis in Bavaria, Pacelli would have little to do with what appeared at the time to be one of any number of fringe political parties. When Hitler was jailed in 1923 after an unsuccessful coup in Munich (the so-called “Beer Hall Putsch”) his career seemed finished. Recalling those early days, Pacelli noted that he – and the rest of the foreign diplomatic corps – paid scant attention to the Munich ruffian. He explained, “In those days, you see, I wasn’t infallible.”10 In 1925, Pacelli moved from Munich to Berlin. By now, however, Pacelli had grown more concerned about the Nazi threat and he reported to Rome that Hitler was a violent man who “will walk over corpses” to achieve his goals. In 1928, the Holy office issued a strong condemnation of the anti-Semitism foundational to the Nazis: “(T)he Holy See is obligated to protect the Jewish people against unjust vexations and…particularly condemns unreservedly hatred against the people once chosen by God; the hatred that commonly goes by the name anti-Semitism.” Pacelli successfully concluded a concordat with the Prussian State in 1929. That year, he returned to Rome to serve as Secretary of State under Pope Pius XI and was named a cardinal. As Secretary of State in the 1930s, Pacelli would be responsible for dealing with both the Fascist government of Italy and Adolf Hitler in Germany. Though the Vatican had negotiated a concordat with Italy in 1929, ending the decades-long break between Italy and the Church, the relationship between Pope Pius XI and Benito Mussolini’s fascist government was anything but cordial. The Church was vociferous in its criticism of Fascist ideology both before and after the concordat. But little attention was paid to such criticism, particularly in the Western countries where Mussolini was viewed as somewhat a hero, both for his stabilization of the Italian economy and his tweaking of the papal nose. Anti-fascist statements by Catholic leadership were viewed as counter-revolutionary, and when Mussolini concluded the concordat, he was criticized outside Italy for his compromise with the Church. In 1931, Pius XI responded to ongoing attacks on the Church by Mussolini’s goons with “Non Abbiamo Bisogno,” (“We have no Need”) an encyclical written in Italian, smuggled out of Italy by Msgr. Francis J. Spellman of New York to be printed and released in Paris. In the encyclical, Pius XI condemned the pagan worship of the state that was central to Fascist ideology.11 Again, the encyclical received scant attention outside of Italy. Despite vocal opposition from the Catholic Church in Germany where National Socialism’s racist views were routinely condemned as contrary to Catholic principles and Catholics were ordered not to support the party, by 1933 Hitler had become German chancellor. Immediately, persecution of the German Jewish population began. Pacelli was dismayed with the Nazi assumption of power and by August of 1933 he expressed to the British representative to the Holy See his disgust with “their persecution of the Jews, their proceedings against political opponents, the reign of terror to which the whole nation was subjected.” When it was stated that Germany now had a strong leader to deal with the communists, Cardinal Pacelli responded that the Nazis were infinitely worse.12 At the same time, however, the Vatican was forced to deal with the reality of Hitler’s rise to power. In June 1933 Hitler had signed a peace agreement with the western powers, including France and Great Britain, called the Four-Power Pact. At the same time Hitler expressed a willingness to negotiate a statewide concordat with Rome. The concordat – highly favorable to the Church – was concluded a month later. In a country where Protestantism dominated, the Catholic Church was finally placed on a legal equal footing with the Protestant churches. The accusation is often made that the concordat negotiated by Cardinal Pacelli gave legitimacy to the Nazi regime. Forgotten is the fact that it was preceded both by the Four-Power Pact and a similar agreement concluded between Hitler and the Protestant churches. The Church had no choice but to conclude such a concordat, or face draconian restrictions on the lives of the faithful in Germany. Cardinal Pacelli denied that the concordat meant Church recognition of the regime. Concordats were made with countries, not particular regimes. Pius XI would explain that it was concluded only to spare persecution that would take place immediately if there was no such agreement. The concordat would also give the Holy See the opportunity to formally protest Nazi action in the years prior to the war and after hostilities began. It provided a legal basis for arguing that baptized Jews in Germany were Christian and should be exempt from legal disabilities. Though the Concordat was routinely violated before the ink was dry, its existence allowed for Vatican protest, and it did save Jewish lives. In the early years of the Holocaust, prior to the outbreak of war, the Nazi program against the Jews (who numbered about 500,000 in Germany, about one percent of the population) involved economic persecution and boycotts. Jews were denied public jobs and, in 1935, were stripped of their rights as citizens. Violence and murder soon followed, culminating in the horror of Kristallnacht in November, 1938, and the first major deportations to concentration camps.13 About half the Jewish population fled Germany during the period between 1933 and 1938, though many would not escape death at Nazi hands as they settled in countries that would eventually be occupied by German forces in the war. The Holy See had begun to lodge protests against Nazi action almost immediately after the concordat was signed. The first formal Catholic protest under the concordat concerned the anti-Jewish boycotts. Numerous protests would follow over treatment of both the Jews and the direct persecution of the Church in Nazi Germany. The German foreign minister would report that his desk was stuffed with protests from Rome, protests rarely passed on to Nazi leadership. In March 1937, Pope Pius XI issued the encyclical Divini Redemptoris, a scathing attack on atheistic communism. The encyclical was immediately followed by Mit Brennender Sorge(“With Burning Concern”), written by Cardinal Pacelli. Mit Brennender Sorge was written in German and secretly distributed to parish priests throughout the country. The encyclical condemned the racist principles of Nazism and the slavish worship of the state. The German government described it as a “call to battle against the Reich.” The Nazi press condemned the “Jew-God and His deputy in Rome” while the government threatened to cancel the concordat. In a Europe still committed to appeasing Hitler, the Church was the only voice speaking out strongly against the Nazis. Also in 1937, Cardinal Pacelli spoke at Notre Dame Cathedral in France and attacked Nazi leadership and the pagan cult of race they espoused. In 1938 when Hitler took over Austria and the Anschluss was welcomed by the Archbishop of Vienna, Cardinal Pacelli brought the archbishop to Rome and demanded a retraction of his statement. Even as the health of Pius XI waned, he stepped up his attacks on Italian Fascism and Nazism. Cardinal Pacelli wrote to archbishops throughout the world in early January 1939 “instructing them to petition their governments to open their borders to Jews fleeing persecution in Germany. The following day Pacelli wrote to American cardinals, asking them to assist exiled Jewish professors and scientists.”14 On February 10, 1939 Pius XI died. In response, the Nazi press called him the “Chief Rabbi of the Western World.”15 In the years between Pacelli’s birth up to the death of Pius XI, there is no record of anti-Semitism on his part.16 With the birth of Nazism, the Church early became a voice strongly in opposition to its racist theories, its worship of the state, and its attacks on the Jews. Pacelli was strongly involved at the highest levels in the papacy of Pius XI that led a vociferous campaign against Fascism in Italy and Nazism in Germany. The Church had become directly involved in the defense of Jews in Germany and had begun to offer its services to refugees fleeing persecution. The Nazis knew Cardinal Pacelli as an ally of Pius XI and a foe. “On February 16, 1939, the German Ambassador to the Holy See…addressed the Sacred College of Cardinals in what was expected to be a customary expression of sympathy over the death of Pius XI. Rather than merely offering condolences, however, the ambassador made…a clear request for a Pope more sympathetic to Hitler’s expansionist plans. The British Legation to the Holy See reported back to London that (the speech)… ‘was a veiled warning against the election of Cardinal Pacelli.’”17 The cardinals ignored the advice. On March 2, 1939 Pacelli was elected and took the name Pius XII. Much of the world cheered while the Nazis were unimpressed. Jewish groups hailed the election, citing Pacelli’s long public record on Nazism and his strong hand in writing Mit Brennender Sorge.

The Papacy of Pope Pius XII In the first months of his papacy, Pius XII would focus his efforts on preventing what seemed an inevitable outbreak of war. Pius XII attempted to arrange a summit in May of the major European powers, but his proposal was turned down. Papal attempts to move Italy and France to negotiations failed. The British and French had assured Poland of assistance if attacked by Germany. Nazi leadership appeared convinced that the two powers would not interfere. On August 21, 1939, the German government announced a non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union. The world was shocked while the Vatican was not surprised. France and Britain wanted the pope to make a strong pro-Polish statement, but, fearing the impact on the millions of German Catholics, he chose to maintain a neutral stance and on August 24th gave a solemn radio talk begging for peace and negotiation. He initiated various approaches to the Polish, British, French, German and Italian governments to attempt to ward off the inevitable invasion of Poland. It was to no avail as there was a general unwillingness to negotiate with a Germany that had proven to be insatiable. On September 1, 1939, Hitler’s troops smashed into Poland from the west while the Soviet Union would quickly begin a land-grab in the east. On September 3, France and Great Britain declared war on Germany.18 Within a month the Polish army was defeated and the true Holocaust began. Polish leadership was killed, along with many Catholic priests. Large segments of the Polish population were resettled and thousands of Poles, including Jews, were herded into concentration camps. While most of Europe would experience the Nazi horror, Poland would live it the longest and suffer the greatest. Poland would also be the site for the Nazi death camps. Jews from all over Europe would be transported to these camps in Poland, and six million would die. Of the total Polish population, three million would die in the death camps, another two million would serve as slave labor in Germany. In the early months of the war, the Pope began to establish committees to help both Catholic and Jewish war refugees and began the Vatican Information Bureau to track down missing civilian population and prisoners. On October 20, 1939, Pope Pius XII issued his first encyclical, Summi Pontificatus. In this encyclical he lashed out at the dictators of Europe – “an ever-increasing host of Christ’s enemies” – and reminded the world of St. Paul’s vision that was neither Gentile nor Jew. The Gestapo labeled the encyclical a direct attack, while the French had copies printed and dropped by air over western Germany. The New York Timessummarized the encyclical as a call for the restoration of Poland and an uncompromising attack on racism and dictators.19 One of the more surprising developments that came to light only later was papal involvement as a middleman between anti-Hitler elements of the German military and the British government. Over the course of several months, Pope Pius XII relayed messages between the anti-Hitler conspirators and the British government. The pope also received information on German military plans that were forwarded on to the Allies, including advance notice of the invasion of France, Luxembourg, Holland and Belgium. While the conspiracy against Hitler did not succeed, it was a startling act of papal intervention.20 Through its sources, the Vatican was growing aware of the Nazi slaughter taking place in Poland. In January, 1940, Vatican Radio was instructed by the pope to broadcast – in German – a detailed report on attacks on the Church and civilians in Poland. A week later, Vatican Radio broadcast to an unbelieving world in English that “Jews and Poles are being herded into separate ghettos” where starvation, disease and exposure would kill tens of thousands. Shortly thereafter, the German Foreign Minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop, demanded a papal audience. On March 11, the pope met with the foreign minister who assured him that a German victory was inevitable in 1940.21 The pope responded with a detailed list of Nazi atrocities in Poland and to German Jews. The New York Times described the meeting with the headline “Pope is Emphatic about Just Peace: Jews’ Rights Defended.”22 On May 10, 1940, the German invasion of France, Holland, Luxembourg and Belgium began. The pope sent telegrams to the three neutral states condemning the unwarranted invasion. The Italian government protested what it saw as a direct attack on its German ally and copies of l’Osservatore Romano containing the texts of the telegrams were seized. Soon after, Mussolini would enter the war. Within a month, France was defeated. In reaction to the Vatican press and radio broadcasts concerning Poland, Germany announced that priests and religious would not be able to leave Poland. Persecution was stepped up. Pius XII issued instructions to the Catholic bishops of Europe to help all suffering at the hands of the Nazis and to remind their people than any form of racism is contrary to Church teachings.23 Pius XII faced an occupied Europe. His focus in the last half of 1940 was on the dreadful situation in Poland, but the Nazi puppet Vichy government in France, and the occupied Benelux nations, were of growing concern. Pius understood the Vichy government’s status in relation to the Nazis and was in opposition virtually from its inception. By the summer of 1941 Vichy would be deporting Jews over strong Vatican protests. In his Christmas message of 1940, the pope once again condemned the war and pleaded for aid to the suffering. In the early months of 1941, the Vatican worked to assure that Spain would not enter the war. It served to mediate a potentially dangerous dispute with the United States and was instrumental in keeping Spain neutral. When Vichy France began to deport Jews Spain would become a haven. It is estimated that Franco’s Spain – though vilified for its fascist leanings and alliance with Hitler during its own revolution – provided safe refuge for possibly a quarter of a million Jews. Hitler would complain about Franco and his “Jesuit swine” foreign minister. In late March 1941, Vatican Radio launched a series of attacks on Nazi Germany, denouncing its principles of racial hatred. A series of misstatements and misuse of Vatican Radio reports, however, raised a concern that the Holy See could be seen as the “enemy” of Germany. Pius XII resisted any perception of the violation of the Holy See’s neutrality in the conflict, though German leadership had decided long ago that the pope was an undeclared enemy. In any case, Vatican Radio was instructed, in the words of Vatican Secretary of State Cardinal Luigi Maglione to “let the facts speak for themselves” and not to enhance or editorialize. The British – who reused edited texts from the Vatican broadcasts for propaganda purposes – protested when such “silencing” was discovered. While the Vatican responded that its broadcasts were being twisted for propaganda purposes, the extent of continued persecution led Vatican Radio to sustained criticism of Nazi tactics, particularly in its persecution of the Jews.24 After Hitler ordered the invasion of the Soviet Union in June, the question quickly arose over aiding communists in the war against the Nazis. The 1937 encyclical of Pius XI appeared to ban any such cooperation. The issue became particularly important in the United States where aid was routinely supplied to the Allies and was to be extended to the Soviet Union. A number of bishops raised the issue and, very quickly, Pius XII settled the affair noting that aid to the “people” of the Soviet Union was not aid to communism. Despite later propaganda, it was clear that even an anti-religious Stalinist Soviet Union was viewed by the pontiff as far less an enemy than the German Third Reich.25 In his Christmas message of 1941, Pius XII issued another forceful call for peace and condemned the atrocities of the war, particularly involving civilian populations. Germany heard it as another attack on Nazism. The New York Times wrote a long editorial, calling Pius “the only ruler left on the Continent of Europe who dares to raise his voice at all.” Noting that “the Pope put himself squarely against Hitlerism…he left no doubt that the Nazi aims are also irreconcilable with his own conception of a Christmas peace.”26

The Final Solution In January 1942, the most horrifying stage in the Final Solution began at the Wannsee Conference in Germany. On January 20th, Gestapo officials under Hitler’s expressed direction formalized plans for the “Final Solution” of the Jewish population of Europe. Just two days later, Vatican Radio launched an attack on conditions in Poland under the Nazis. The Polish bishops, however, began to quietly urge the Vatican to avoid such public pronouncements.27 The pope was notified that the Gestapo said that Vatican Radio had called for Polish resistance and for “the Polish people to rally around its priests and teachers. Thereupon, numerous priests and teachers were arrested and executed, or were tortured to death in the most terrible manner, or were even shipped to the far east.”28 After the Wannsee conference, the Nazis began to step up the deportation of Jews in occupied territories. Since the beginning of Nazi atrocities against the Jews, the Vatican had pursued attempts to help Jews emigrate from German-controlled areas. It now became clear that the goal must be to prevent deportation. Reports had begun to reach the Vatican that there was a gruesome end to such deportations. Those deported virtually vanished. Relatives received no news of their family. In early March 1942, a major deportation was begun in Slovakia. The Vatican, through the local nuncio, desperately protested but to no avail. Reports from the nuncio within Germany told of the horrible situation of the remaining Jews, whether they be Catholics through Baptism or not. Protests by the nuncio were dismissed, the Nazis unwilling to even address where those deported had been sent, let alone their faith. As Father Blet described the Vatican’s frustration, in Germany “any step was fruitless and even dangerous.” In France, as the deportations began, Church authorities with the support of Pius XII protested throughout the summer of 1942. Vatican Radio and l’Osservatore Romanoreported on powerful statements such as that of Archbishop Jules Saliege in Toulouse who complains that “frightful things are taking place. The Jews are our brothers. They belong to mankind. No Christian can dare to forget that!” In July, the bishops and cardinals of France signed a formal protest to the government over the deportations. Angered at Church intervention, Vichy authorities dismissed the Church’s protest and the arrests and deportations continued. In Holland, the bishops spoke out forcefully against the deportation of the Jews with disastrous results. The Catholic archbishop of Utrecht released a forceful letter to all the Catholic churches protesting the deportations of the Jews. The Gestapo responded by revoking the exception that had been given to Jews who had been baptized and a round up was ordered. Caught in the web was Edith Stein, a Jewish convert who had become a nun. She, her sister, and 600 Catholic Jews were transported to Auschwitz, where she died.29 The deportations of all Jews were expanded and by the end of the war virtually the entire Jewish population of Holland had been wiped out. The disaster in Holland and the ineffectiveness of the French intervention did not deter Pius XII from continuing to work in whatever way possible to assist the persecuted Jews. They did, however, confirm the view that dramatic public statements in specific situations should be avoided. Such statements were easy to make, Pius believed, but could cause untold suffering. For the most part, Pius would rely on Church authorities on the scene to determine the best action and follow their course. This included the web of nuncios reporting directly to Rome from capitals throughout Europe who would become the primary source of papal action and activity. It would be these nuncios under papal direction that would save untold Jewish lives in the years ahead. Additionally, there was the practical realization that it was virtually impossible to deal with the Nazi authorities. Greater success was possible in working in occupied countries with their own governments in place. One could at least approach the Vichy government, for example. One could do nothing in Germany. In September 1942, Pius XII was approached by the Allies to join in a statement condemning the Nazi atrocities. This was to be an official statement of the Allied governments and it was impossible for Pius XII, representing a neutral state, to join the effort. However, in his annual Christmas message of 1942, Pius XII would speak out once again forcefully. Without specifically mentioning Hitler, Pius condemned totalitarian regimes and mourned the victims of the war: “the hundreds of thousands who, through no fault of their own, and solely because of their nation or race, have been condemned to death or progressive extinction.” He called on Catholics to shelter any and all refugees. The statement was loudly praised in the Allied world. In Germany, it was seen as the final repudiation by Pius XII of the “new order” imposed by the Nazis. “(H)e is virtually accusing the German people of injustice toward the Jews, and makes himself the mouthpiece of the Jewish war criminal.”30 Beginning in 1943, evidence mounted of the mass extinction of the Jews under Nazi control, particularly of the use of gas chambers in concentration camps. Though the allied governments refused to acknowledge such a reality, a desperation is evidenced in the Vatican and throughout the nunciatures. With Germany beginning to experience defeat on the battlefield, pressure was stepped up on the puppet regimes to facilitate the Final Solution by increased deportations. On February 19, Vatican Radio condemned deportations and promised “the curse of God” on those who did such things.31 In Poland, the Church had virtually been destroyed by mid 1943. The Vatican prepared a detailed report of its plight and sent it on in protest to the German authorities, who refused to even acknowledge its receipt. In June, Pius XII publicly lamented the “tragic fate” of the Polish people. There was no longer structure to contact or an organization through which the Church could work. By the “second half of 1943 communications became more and more uncertain between the Poles in Poland and the Holy See, which was progressively losing all contact with the bishops…Contact with eastern Poland, which was already almost completely under the control of the Red Army, was even more difficult.”32 “(I)n Germany…papal interventions were simply useless…They were predestined to failure in the face of the inflexible decisions made by the national-socialist state. But between the two Axis powers…there were also regions that in various degrees had fallen under control of the Reich and within which the Holy See nonetheless felt it could exercise an influence and counteract the designs of the Berlin government. This was true for the…Axis satellites, namely Slovakia, Croatia, Romania and Hungary.”33 In Slovakia, the Holy See faced the unique difficulty of its president, Joseph Tiso, being a Catholic priest. In September 1941 the Vatican was informed that laws against the Jews were to be passed. The nuncio was instructed to protest immediately, reminding Tiso that such legislation was “directly opposed to Catholic principles.” The protest was ignored and in early 1942, the nuncio informed the Vatican that deportations, in which the Germans promised to “treat the Jews humanely,” would be forthcoming. Cardinal Maglione protested to the Slovakian representative while the nuncio was to protest to Tiso. Tiso promised to spare as many as possible. The bishops of Slovakia released an officially edited pastoral letter with one important sentence retained: “The Jews are also people and consequently should be treated in a humane fashion.” While the intervention helped to save baptized Jews and those married to non-Jews, thousands were deported in 1942. In 1943, when rumors of a new deportation surfaced, the Vatican again sharply protested. The government responded that rumors of internment camps and executions were “Jewish propaganda.” The Vatican refused to let up and the deportation orders were lifted. As the summer of 1944 ended, there was an uprising in Slovakia that was crushed by German troops. The Jews were under great threat and the nuncio once again appealed to Tiso. Tiso blocked some deportations at first, then relented to German pressure. Pope Pius XII drafted a personal appeal to Tiso to be handed on by the nuncio. It accomplished nothing.34 In Croatia, the position of the 40,000 Jews was more precarious. The attempt was made through Cardinal Maglione to bring the Jewish population to Italy. Those Croatian Jews in territories occupied by Italian troops were protected. In the summer of 1942, the papal envoy to Croatia protested to the president about the treatment of the Jews. In a strange meeting, the president stated that Jews had been transferred to Germany where the government had recently “destroyed” two million. The horrified nuncio reported this to the Holy See. Shortly thereafter, he could report that he had some limited success in obtaining exceptions to additional deportations of Jews, including many that had not been baptized. In 1943, the situation appeared to have improved until Croat authorities lashed out at Vatican intervention when the nuncio protested a new Jewish round up. While the Vatican was able to save a small number of Jews, most were subsequently deported.35 Throughout June 1943 Vatican Radio called for an end to attacks on Jews, particularly in the Axis satellites. At the demand of the Holy See the papal nuncio to Germany, Cesare Orsenigo, was finally granted an audience with Hitler. His instructions were to plead for better treatment for the Jews in Germany and the occupied territories. He reported to the Vatican: “A few days ago I was…received by Hitler; as soon as I touched upon the Jewish question, our discussion lost all sense of serenity. Hitler turned his back on me, went to the window and started to drum on the glass with his fingers…while I continued to spell out our complaints. All of a sudden, Hitler turned around, grabbed a glass off a nearby table and hurled it to the floor with an angry gesture…”36 In Romania, the Vatican had the benefit of a concordat, though the Catholic population was small. By 1941, anti-Semitic legislation was already in place when the government announced a law forbidding Jews to change their religion. At the request of Cardinal Maglione, the nuncio protested and the restriction was lifted. For obvious reasons, the number of Jews requesting baptism rose rapidly and in the Spring of 1942 the government protested. The nuncio responded that Pius XII could not refuse any request for admission to the Church. The nuncio intervened often to prevent as much as possible attacks on the non-baptized Jews and developed a close relationship with the leadership of the Romanian Jews. Romanian Jews never faced deportation to Poland. Under the direction of Cardinal Maglione “to mitigate those measures so opposed to the teaching of Christian morality,” the nuncio in 1943 protested a deportation of Jews, many of them orphaned children, to the coast. He also continued to protest any government attempt to limit or interfere with Jews who requested instruction and baptism. By 1944, the fear was real that with a deteriorating military situation, the Jews within internal Romanian camps would fall under German control, including thousands of Jewish orphans. Through the Holy See’s intervention, a number were transported safely to Istanbul. While anti-Jewish legislation was a part of Hungarian life as early as 1939, “mass deportations of Jews did not take place till the Reich had taken complete control of the country in 1944.”37 The nuncios to both Hungary and Romania were warned by the Secretary of State that the German presence meant increased pressure for complete deportation of the two million Jews combined in each country. In Hungary, the nuncio bitterly complained of the planned deportation to Auschwitz to the prime minister, charging such persecution as contrary to natural law. The minister refused any consideration, including exemption for baptized Jews. At the instruction of the Vatican the nuncio forcefully repeated the request, demanding humane treatment of the Jews and exemption for those Jews who had been baptized. The deportations continued and the nuncio recommended a direct and public intervention from the Holy See. On June 12, 1944, Pope Pius XII addressed an open telegram to Admiral Horthy, regent of Hungary, requesting an end to the deportations and the sufferings “endured by a large number of unfortunate people due to their nationality or race.” Horthy discontinued the deportations and it estimated that 170,000 Hungarian Jews were saved. Horthy, however, was losing control in Hungary. Soon, limited deportations began again and the nuncio mobilized a large diplomatic protest. Horthy responded that he would continue to resist German demands for deportations. Shortly thereafter, Horthy announced an armistice with the Soviet Union. He was immediately arrested and the Nazis assumed command. Rumors spread that 300,000 Jews were to be deported. The Pope again issued a public plea, joined with that of the Hungarian bishops, to support and give all possible assistance to the Jews, baptized or not. In November 1944, the nuncio continued to publicly protest and joined with five neutral powers to present a formal letter of protest over the treatment of the Jews. The nuncio’s office supplied over 13,000 letters of protection, which held off the deportation of many Jews. With the Red Army at the very gates of Budapest, anti-Jewish deportations continued and the nuncio continued to protest. “(T)he Jewish leaders recognized the pope’s efforts on behalf of their persecuted communities, and that despite repeated failures and limited results, the Holy See’s actions were not completely in vain. Still more remarkable in a way is that, despite the fact that so many repeated interventions ended with only tenuous results in comparison with the efforts expended, the Vatican in the midst of the uncertainty and the darkness within which it had to take action, continued its lifesaving work to the end.”38 In Italy, the situation for the Jews was far better than on most of the continent. While anti-Semitic laws were enacted prior to the war, the Holy See successfully fought for many exemptions. Mussolini’s government was for the most part not strongly committed to anti-Semitic persecution, and the Italian people themselves even less so. During the early stages of the war, many Jews fleeing the Nazis would come to Italy, though this immigration would end over time. The Italian government would for the most part refuse to deport those Jews under its authority. In June 1943, the Allied invasion of Italy began and by July, Mussolini’s government had fallen. A new regime took his place and in September would sign an armistice and in October declare war on Germany. The Germans, however, remained and put up strong resistance. That summer, 60,000 German troops entered Rome. “This is when the Church undertook a relief effort which has been called ‘probably the greatest Christian program in the history of Catholicism.’ Pius sent a letter by hand to the bishops instructing them to open all convents and monasteries throughout so that they could become safe refuges for Jewish people. All available church buildings – including those in Vatican City – were put to use. One hundred and fifty such sanctuaries were opened in Rome alone. Castel Gondolfo, the Pope’s normal summer home, was used to shelter about 500 Jews, and several children were born in his personal apartment…Almost 5,000 Jews, a third of the Jewish population of Rome, were hidden in buildings that belonged to the Catholic Church.”39 Throughout Italy, Jews were hidden, disguised (some were dressed as clerics and taught Gregorian chant) and provided with false documents to escape to Spain or Switzerland. On Saturday, October 16, 1943, the Gestapo in Rome began a round up of those Jews not in hiding. Within a short time, 1,259 Jews were captured. Upon being informed, Pope Pius XII immediately filed a protest with the German ambassador, Ernst von Weizsäcker. The ambassador had little interest in encouraging Nazi persecution. He assured Cardinal Maglione that a number of the Jews had already been released and the arrests would cease. The ambassador warned Pius XII through the cardinal not to make a public demonstration as this would only serve to inflame the Nazi authorities and threaten the lives of the Jews in hiding throughout Rome. Weizsacker would purposely downplay to German authorities the pope’s complaints and often pocket protests to avoid increased persecution. It is estimated that 40,000 Jewish lives were saved in Italy through the intervention of Pius XII.

Pius XII and the Holocaust The major accusation made against Pius XII in regard to the Holocaust is that the pope refused to speak out publicly and if he had done so, lives would have been saved. Both points are flawed. Pope Pius XII did speak out long before any statements were made, even by Allied governments. There was no “papal silence” and that is a canard created by an anti-Catholic dramatist two decades later. At the same time, however, Pius XII did not believe that words were the most appropriate means to save lives. He believed in action and work behind the scenes and at the scene through the papal nuncios. Issuing thunderbolts from the safety of the Vatican aimed at the Nazis would have done nothing to end the “Final Solution” and could have severely limited, if not ended altogether, the Church’s capacity to save lives, particularly in the Axis satellite states. CBS correspondent Edward Bradley in the “60 Minutes” report on Pius XII argued that Pope Pius XII should have stood in front of the train that deported a thousand captured Roman Jews, arguing that a saint would have done just that. Ambassador Weizsacker had his own response from the very time it took place: “A ‘flaming protest’ by the Pope would not only have been unsuccessful in halting the machinery of destruction but might have caused a great deal of additional damage – to the thousands of Jews hidden in the Vatican and the monasteries…and – last but not least – to the Catholics in all of Germany-occupied Europe.”40 The pope himself, possibly foretelling today’s accusations, once noted after the war, “No doubt a protest would have gained me the respect of the civilized world, but it would have submitted the poor Jews to an even worse fate.” History is what history was. Would incessant public statements from the lips of Pius XII have accomplished a greater good? Cornwell argues that such statements could have led to a “Catholic uprising” that could have halted Hitler. That is highly doubtful conjecture. What the Church was able to accomplish in World War II under the direction of Pius XII was what no other agency, government or entity at the time was able to accomplish: saving Jewish lives. Pulitzer Prize winning historian John Toland, no friend of Pius XII, summed it up: “The Church, under the Pope’s guidance…saved the lives of more Jews than all other churches, religious institutions and rescue organizations combined…The British and the Americans, despite lofty pronouncements, had not only avoided taking any meaningful action but gave sanctuary to few persecuted Jews.” 41 “Lofty pronouncements” saved no lives during the horror of the Holocaust. Action did so. Pinchas Lapide, Israeli consul in Italy, estimated that the actions of Pius II saved over 800,000 Jewish lives during World War II. If that were an exaggeration by half, it would record more Jewish lives saved than by any other entity at the time.

A note on sources This Catholic League documentation relied heavily on important direct research accomplished by others, including the magazine Inside the Vatican whose editors put together a strong special issue in October 1999 on the topic of Pius XII and the Holocaust. Sister Margherita Marchione has written Yours Is a Precious Witness and Pius XII: Architect for Peace (available from Paulist Press). Both are remarkable studies on Church efforts to save Jewish lives and the pontificate of Pope Pius XII. Also available from Paulist Press isPius XII and the Second World War, a translation by Lawrence J. Johnson of Father Pierre Blet’s extraordinary study of the Vatican archival record of the war years. Finally, Hitler, the War and the Pope (Genesis Press, August 2000) by Ronald Rychlak is the definitive popular history of the papacy of Pope Pius XII in the shadow of Nazism. Without recourse to rhetoric, Rychlak gives a well-documented and clear-headed defense of Pius XII. His book also provides a detailed response to John Cornwell’s Hitler’s Pope. Rychlak’s work puts the claim of the “silence” of Pope Pius XII in the face of the Holocaust to rest.

SUMMARY POINTS *For nearly 20 years after World War II, Pope Pius XII (1939-1958) was honored by the world for his actions in saving countless Jewish lives in the face of the Nazi Holocaust. *A sampling of some of the Jewish organizations that praised Pope Pius XII at the time of his death for saving Jewish lives during the horror of the Nazi Holocaust: the World Jewish Congress, the Anti-Defamation League, the Synagogue Council of America, the Rabbinical Council of America, the American Jewish Congress, the New York Board of Rabbis, the American Jewish Committee, the Central Conference of American Rabbis, the American Jewish Committee, the Central Conference of American Rabbis, the National Conference of Christians and Jews and the National Council of Jewish Women. *When critics are reminded of the universal praise he received from Jewish organizations in life and death, they are dismissed as merely “political” statements, as if those Jews who had lived through the Holocaust would insult the memory of the millions killed for some ephemeral political gain. *Contemporary Catholics are witnessing the creation of a myth in regard to Pius XII, a propaganda campaign as relentless as any created by 19th century anti-Catholic apologists. *The myth of Pius XII began in earnest in 1963 in a drama created for the stage by Rolf Hochhuth, an otherwise obscure German playwright born in 1931. In The DeputyHochhuth charged through a fictional presentation that Pius XII maintained an icy, cynical and uncaring silence during the Holocaust. More interested in Vatican investments than human lives, Pius was presented as a cigarette-smoking dandy with Nazi leanings. *Even John Cornwell in Hitler’s Pope describes The Deputy as “historical fiction based on scant documentation…(T)he characterization of Pacelli (Pius XII) as a money-grubbing hypocrite is so wide of the mark as to be ludicrous. Importantly, however, Hochhuth’s play offends the most basic criteria of documentary: that such stories and portrayals are valid only if they are demonstrably true.” *The Deputy was used as a means to discredit an anti-Communist papacy. Instead of Pius being seen as a careful and concerned pontiff working with every means available to rescue European Jews in the face of complete Nazi entrapment, an image was created of a political schemer who would sacrifice lives to stop the spread of Communism. *When The Deputy appeared the Jewish world had experienced a virtual re-living of the Holocaust in the trial of Adolf Eichmann. For many young Jews, Eichmann’s trial was the first definitive exposure to the horror that the Nazis had implemented. In the United States Jewish community, as well as in Israel, Hochhuth’s charges of a papal “silence” and indifference during the Holocaust were readily accepted. Despite the fact of a two-decades-old acknowledgment of papal support and assistance to the Jews during the War, Hochhuth’s unfounded charges took on all the aspects of revelation. *While nothing can fully destroy the enormous strides taken by Pope John Paul II, leaving this myth unanswered and accepted can only do great damage to what should be a deep and close relationship between Catholics and Jews. *Eugenio Pacelli reported to Rome from Germany that Hitler was a violent man who “will walk over corpses” to achieve his goals. In 1928, the Holy office issued a strong condemnation of the anti-Semitism foundational to the Nazis: “(T)he Holy See is obligated to protect the Jewish people against unjust vexations and…particularly condemns unreservedly hatred against the people once chosen by God; the hatred that commonly goes by the name anti-Semitism.” *Pacelli was dismayed with the Nazi assumption of power and by August of 1933 he expressed to the British representative to the Holy See his disgust with “their persecution of the Jews, their proceedings against political opponents, the reign of terror to which the whole nation was subjected.” When it was stated that Germany now had a strong leader to deal with the communists, Cardinal Pacelli responded that the Nazis were infinitely worse. *The Holy See had begun to lodge protests against Nazi action almost immediately after the concordat was signed with Germany. Its first protest concerned the government-directed anti-Jewish boycotts. Numerous protests would follow over treatment of both the Jews and the direct persecution of the Church in Nazi Germany. The German foreign minister would report that his desk was stuffed with protests from Rome, protests rarely passed on to Nazi leadership. *In 1937, Pope Pius XI issued the encyclical Mit Brennender Sorge (“With Burning Concern”). Drafted by Cardinal Pacelli, Mit Brennender Sorge was written in German and secretly distributed to parish priests throughout the country. The encyclical condemned the racist principles of Nazism and the slavish worship of the state. The German government described it as a “call to battle against the Reich.” *The Nazi press condemned the “Jew-God and His deputy in Rome” while the government threatened to cancel the concordat. In a Europe still committed to appeasing Hitler, the Church was the only voice speaking out strongly against the Nazis. *Cardinal Pacelli wrote to archbishops throughout the world in early January 1939 instructing them to petition their governments to open their borders to Jews fleeing persecution in Germany. The following day Pacelli wrote to American cardinals, asking them to assist exiled Jewish professors and scientists. *On October 20, 1939, Pope Pius XII issued his first encyclical, Summi Pontificatus. In this encyclical he lashed out at the dictators of Europe – “an ever-increasing host of Christ’s enemies” – and reminded the world of St. Paul’s vision of neither Gentile nor Jew. The Gestapo labeled the encyclical a direct attack, while the French had copies printed and dropped by air over western Germany. The New York Times summarized the encyclical as a call for the restoration of Poland and an uncompromising attack on racism and dictators. *In January, 1940, Vatican Radio was instructed by the pope to broadcast – in German – a detailed report on attacks on the Church and civilians in Poland. A week later, Vatican Radio broadcast to an unbelieving world in English that “Jews and Poles are being herded into separate ghettos” where starvation, disease and exposure would kill tens of thousands. *In 1940, Pius XII issued instructions to the Catholic bishops of Europe to help all suffering at the hands of the Nazis and to remind their people than any form of racism is contrary to Church teachings. *In the early months of 1941, the Vatican worked to assure that Spain would not enter the war. It served to mediate a potentially dangerous dispute with the United States and was instrumental in keeping Spain neutral. When Vichy France began to deport Jews Spain would become a haven. It is estimated that Franco’s Spain – though vilified for its fascist leanings and alliance with Hitler during its own revolution – provided safe refuge for possibly a quarter of a million Jews. *After Hitler invaded the Soviet Union, questions were raised concerning aid to the Communist nation, particularly in the United States. A number of bishops raised the issue and, very quickly, Pius XII settled the affair noting that aid to the “people” of the Soviet Union was not aid to communism. Despite later propaganda, it was clear that even an anti-religious Stalinist Soviet Union was viewed by the pontiff as less an enemy than the German Third Reich. *In his Christmas message of 1941, Pius XII issued another forceful call for peace and condemned the atrocities of the war, particularly on the civilian populations. *Germany fumed over another attack on Nazism. The New York Times wrote a long editorial, calling Pius “the only ruler left on the Continent of Europe who dares to raise his voice at all.” Noting that “the Pope put himself squarely against Hitlerism…he left no doubt that the Nazi aims are also irreconcilable with his own conception of a Christmas peace.” *Since the beginning of Nazi atrocities against the Jews, the Vatican had pursued attempts to help Jews emigrate from German-controlled areas. In 1942, it became clear that the goal must be to prevent deportation. Reports had begun to reach the Vatican that there was a gruesome end to such deportations. Those deported virtually vanished. *In France, as the deportations began, Church authorities with the support of Pius XII protested throughout the summer of 1942. Vatican Radio and l’Osservatore Romanoreported on powerful statements such as that of Archbishop Jules Saliege in Toulouse who complains that “frightful things are taking place. The Jews are our brothers. They belong to mankind. No Christian can dare to forget that!” In July, the bishops and cardinals of France signed a formal protest to the government over the deportations. *In Holland, the bishops spoke out forcefully against the deportation of the Jews with disastrous results. The Gestapo responded by revoking the exception that had been given to Jews who had been baptized and a round up was ordered. Caught in the web was Edith Stein, a Jewish convert who had become a nun. She, her sister, and 600 Catholic Jews were transported to Auschwitz, where she died. The deportations of all Jews were expanded and by the end of the war virtually the entire Jewish population of Holland had been wiped out. *After Holland, Pope Pius XII was convinced that dramatic public statements in specific situations should be avoided. Such statements were easy to make, Pius believed, but could cause untold suffering. For the most part, Pius would rely on Church authorities on the scene to determine the best action and follow their course. This included the web of nuncios reporting directly to Rome from capitals throughout Europe who would become the primary source of papal action and activity. It would be those nuncios working with the Vatican that would save hundreds of thousands of Jewish lives. *In his annual Christmas message of 1942, Pius XII condemned totalitarian regimes and mourned the victims of the war: “the hundreds of thousands who, through no fault of their own, and solely because of their nation or race, have been condemned to death or progressive extinction.” He called on Catholics to shelter any and all refugees. The statement was loudly praised in the Allied world. In Germany, it was seen as the final repudiation by Pius XII of the “new order” imposed by the Nazis. “(H)e is virtually accusing the German people of injustice toward the Jews, and makes himself the mouthpiece of the Jewish war criminal.” *On February 19, 1943 Vatican Radio condemned deportations and promised “the curse of God” on those who did such things. *In Germany papal interventions were simply useless. They were predestined to failure in the face of the inflexible decisions made by the national-socialist state. But between the two Axis powers, there were also regions that in various degrees had fallen under control of the Reich and within which the Holy See nonetheless felt it could exercise an influence and counteract the designs of the Berlin government. This was true for the Axis satellites, namely Slovakia, Croatia, Romania and Hungary. *As the summer of 1944 ended, there was an uprising in Slovakia that was crushed by German troops. The Jews were under great threat and the nuncio appealed to Tiso. Tiso blocked some deportations at first, then relented to German pressure. Pope Pius XII drafted a personal appeal to Tiso to be handed on by the nuncio. It accomplished nothing. *On June 12, 1944, Pope Pius XII addressed an open telegram to Admiral Horthy, regent of Hungary, requesting an end to the deportations and the sufferings “endured by a large number of unfortunate people due to their nationality or race.” Horthy discontinued the deportations and it estimated that 170,000 Hungarian Jews were saved. *The Jewish leaders recognized the pope’s efforts on behalf of their persecuted communities, and that despite repeated failures and limited results, the Holy See’s actions were not completely in vain. Still more remarkable in a way is that, despite the fact that so many repeated interventions ended with only tenuous results in comparison with the efforts expended, the Vatican in the midst of the uncertainty and the darkness within which it had to take action, continued its lifesaving work to the end. *In the summer of 1943, 60,000 German troops entered Rome. This is when the Church undertook a relief effort which has been called “probably the greatest Christian program in the history of Catholicism.” Pius XII sent a letter by hand to the bishops instructing them to open all convents and monasteries throughout so that they could become safe refuges for Jewish people. All available church buildings – including those in Vatican City – were put to use. One hundred and fifty such sanctuaries were opened in Rome alone. Castel Gondolfo, the Pope’s normal summer home, was used to shelter about 500 Jews, and several children were born in his personal apartment. Almost 5,000 Jews, a third of the Jewish population of Rome, were hidden in buildings that belonged to the Catholic Church. *It is estimated that 40,000 Jewish lives were saved by the action of Pius XII in Italy. *Pope Pius XII spoke out long before any statements were made, even by Allied governments. There was no “papal silence” and that is a canard created by an anti-Catholic dramatist two decades later. At the same time, however, Pius XII did not believe that words were the most appropriate means to save lives. He believed in action and work behind the scenes and at the scene through the papal nuncios. *What the Church was able to accomplish in World War II under the direction of Pius XII was what no other agency, government or entity at the time was able to accomplish: saving Jewish lives. Pulitzer Prize winning historian John Toland, no friend of Pius XII, summed it up: “The Church, under the Pope’s guidance…saved the lives of more Jews than all other churches, religious institutions and rescue organizations combined…The British and the Americans, despite lofty pronouncements, had not only avoided taking any meaningful action but gave sanctuary to few persecuted Jews.”

FOOTNOTES 1Yours Is a Precious Witness, Margherita Marchione (Paulist Press, 1997), p.57. 2Cited in numerous references, including “The Selling of a Myth,” Ronald Rychlak, Inside the Vatican, October, 1999. 3New York Times, March 14, 2000, p. 28. 4See Faith and Treason, Antonia Fraser (Doubleday, 1996). 5New York Times, March 14, 2000. 6″Is It Enough to be Sorry?” Lance Morrow, Time magazine, March 27, 2000. 7Cornwell, p. 375. 8″Another Pope Visits Jerusalem” Uri Dromi, The Miami Herald, March 20, 2000. 9There is not presently available in English a scholarly biography of Pope Pius XII. Biographical resources for this paper were taken from Catholic Almanac 2000 (Our Sunday Visitor), The Catholic Encyclopedia (Catholic University of America, 1967), and Hitler, the War and the Pope, Ronald Rychlak (Genesis Press, August 2000). 10Cited in Pius XII: Greatness Dishonored, Michael O’Carroll (Laetare Press, 1980) p. 33. 11Rychlak 12Ibid. 13Adolf Hitler, John Toland (Ballantine Books, 1984) pp. 363-376. 14Rychlak 15Ibid. 16In Hitler’s Pope Cornwell quotes from a report within the Vatican archives by Pacelli in his early years at Munich. The letter from Pacelli reports on a meeting his associate had with the violent revolutionaries that had assumed power briefly in Munich in 1919. The letter notes that the revolutionaries were Jews. Cornwell contends that the reference to their Jewishness is representative of “stereotypical anti-Semitic contempt.” Such an interpretation is Cornwell’s alone. The report reads as an objective – if excited – description of what in fact took place and the personalities involved. For a public life of 82 years, no evidence has ever been found of anti-Semitic expression or beliefs in Pius XII. Even Hochhuth at his most vindictive never claimed that Pius was personally anti-Semitic. 17Rychlak 18See William L. Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (Simon and Schuster, 1959 and later editions), pp. 513-597. 19New York Times, January 23, 1940. 20See Toland, pp. 427-428. 21Pius XII and the Second World War, by Pierre Blet, SJ (Paulist Press, 1999). Father Blet’s work is a detailed study of the archives of the Vatican during World War II and a vital source for a proper understanding of the diplomatic activity of the Holy See during the war. 22New York Times, March 14, 1940. 23Cited in Inside the Vatican, October, 1999. 24Blet, pp. 97-104. 25Ibid. pp. 119-127. 26New York Times, December 25, 1941. 27Rychlak 28Ibid. 29She was canonized a martyr/saint by Pope John Paul II in 1998. 30Rychlak 31Inside the Vatican, October 1999. 32Blet, p. 91. 33Ibid. p. 168. 34Ibid. pp. 168-178. 35Ibid. pp. 178-181. 36Rychlak 37Blet, p. 189 38Ibid. p. 200. 39Rychlak 40Cited in Rychlak. 41Toland, p. 549. |

| Copyright © 1997-2011 by Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights. *Material from this website may be reprinted and disseminated with accompanying attribution. |