Ronald J. Rychlak

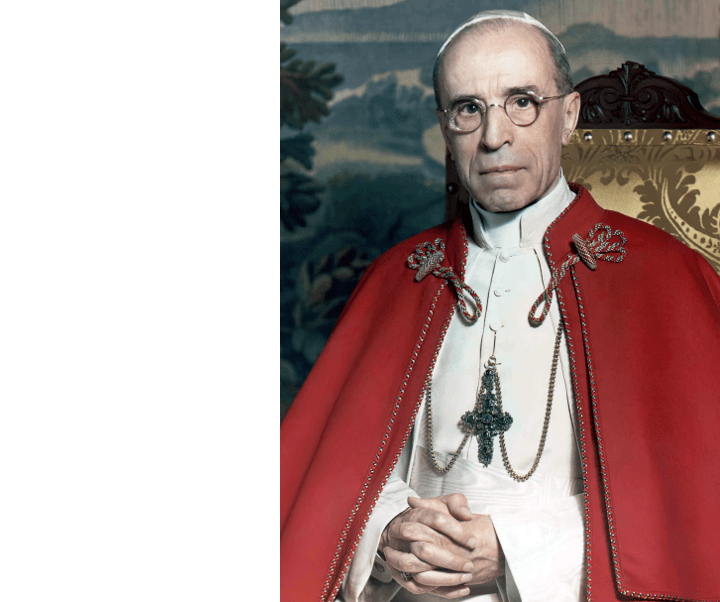

Last week, Amna Nawaz of PBS interviewed David Kertzer, author of a new book on Pope Pius XII and his dealings with the Nazis. We invited Ron Rychlak, Mississippi University law professor and member of the Catholic League’s board of advisors, to respond to the interview. He is one of the nation’s most prominent authorities on this subject.

The argument over Pope Pius XII and his leadership of the Catholic Church during World War II is once again in the news. This time it is driven by a book written by David Kertzer, a professor of anthropology and Italian studies at Brown University. The book is called The Pope at War: The Secret History of Pius XII, Mussolini, and Hitler.

Kertzer was one of the first researchers to explore newly opened archives from the papacy of Pius XII, and his book includes some interesting information. The author acknowledges that it does not contain a single “smoking gun”, but that has not prevented headlines like this one from the PBS News Hour: “Vatican documents show secret back channel between Pope Pius XII and Adolph Hitler.” In the associated interview, Kertzer says that his “most shocking finding” from the newly opened archives is that within weeks of Pius XII’s 1939 coronation, Hitler sent Prince Phillip of Hesse to engage in negotiations with the Vatican.

Surprise, surprise, the pope negotiated with the prince. Of course he did! Some commentators have read this as evidence of a friendly relationship between Pius and the Nazi leader. It was no such thing. Pius understood that his Church and her mission were seriously threatened by the regime. He wanted to assure the safety of those people in his charge and the ability of the Church to continue saving souls.

Consider Pope Francis’s recent agreement with the Communist Chinese government. It is not an endorsement of the Communist Chinese government; he wants to protect his Church and his people. Similarly, his reluctance to condemn Putin by name is not an approval of Russian aggression. It is recognition that such words would not favorably impact Putin’s behavior.

The negotiations about which Kertzer writes took place in 1939-41, before the final solution and the death camps. Pius did not know how Nazi persecution would evolve, and by maintaining relations with the German government, he hoped to push things in a favorable direction.

Kertzer says of the negotiations, “we didn’t know about these until just now.” That’s not completely true. Italy’s Foreign Minister, Count Ciano, made reference to the negotiations in his wartime diary, and Jonathan Petropoulos analyzed them in his 2006 book, noting that “Polish clerics were already suffering tremendously at this time,” and the pope might have hoped to improve the situation. This is a matter worthy of study, and thanks are due to Kertzer for finding more information, but the pre-publication articles and interviews are asserting matters well beyond what the evidence justifies. (And there is nary a mention of Pius XII’s involvement in the efforts to assassinate Hitler.)

The other significant episode the PBS interview focuses on is the October 16, 1943, roundup of Roman Jews. This started with the Nazis demanding 50 kilograms of gold to assure that there would be no deportations. Fearing the worst, the Chief Rabbi of Rome approached the Vatican. Pope Pius XII agreed to an unlimited interest-free loan even though everyone knew that it could not be repaid anytime soon.

Unfortunately, the ransom merely bought a bit of time. As Kertzer explained, “On October 16, 1943, the S.S. had lists of all the Jews in Rome, and went door to door and tried to arrest all of Rome’s Jews, thousands of them.” They were successful in arresting about 1,260. According to Kertzer, “What we now learn from these recently opened archives is that the Vatican worked very hard to show that some of them had been baptized and therefore shouldn’t be considered Jews….” Under Church teaching, anyone who was baptized as a Catholic was a Catholic, regardless of heritage. Those were the people for whom the Vatican had standing with the Germans. It does not mean that these were the only people about whom the pope cared.

Immediately upon learning of the roundups, Pius filed protests through three channels. In the PBS interview, Kertzer gave a brief account of only one of them, Cardinal Secretary of State Maglione’s meeting with German Ambassador Weizsäcker, in which he demanded that the Germans “stop these arrests at once.”

It has long been known that Weizsäcker asked Maglione for permission not to report this conversation back to his German superiors, and the cardinal agreed. Kertzer leaves the impression that this means the Church was not seriously concerned about the arrestees. That is most unfair.

When Weizsäcker made the request, he had already told Maglione that he was “attempting to do something for the unfortunate Jews.” Maglione thanked him for that and left the next step to Weizsäcker’s judgment. A different response would not have assured a better result. Weizsäcker later explained, “Any protest by the Pope would only result in the deportations being really carried out in the thoroughgoing fashion. I know how our people react in these matters.”

The new archives should shed light on this sad period of human history. Unfortunately, abbreviated accounts reported in news stories that are intended to sell books are more likely to produce heat. Fear not. The truth may take longer, but it will come out.