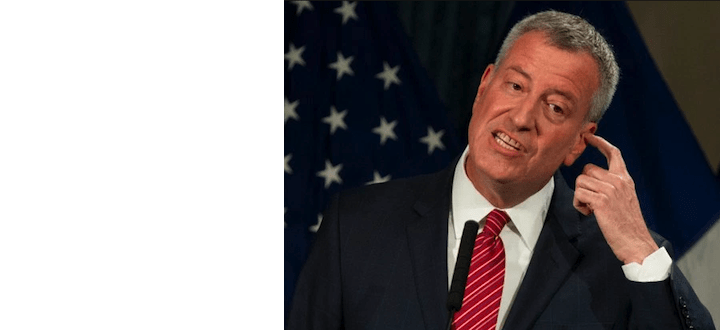

Catholic League president Bill Donohue comments on remarks recently made by New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio on sexual misconduct:

New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio has irked some of his supporters by saying that accusations of sexual harassment made by employees of the Department of Education (DOE) are often false. Though he tried to walk back his comments—the teachers union came down his throat—what he initially said needs to be taken seriously.

De Blasio maintains that this phenomenon is more common among educators than it is among other city employees. Is he right? And if so, what are the implications for assessing sexual misconduct claims made by educators, in general?

No one disputes the data. Between July 2013 and the end of 2017, 471 complaints of sexual harassment were made by the DOE, but only seven, or 1.5 percent, were substantiated.

Responding to the data, Mayor de Blasio said, “On many fronts, we get a certain number of complaints that are not real.” He’s right. This is obviously true of accusations made against priests as well, though anyone who voices this concern is stigmatized for doing so.

De Blasio continued, asserting that “it is a known fact that unfortunately there’s been a bit of a hyper-complaint dynamic sometimes for the wrong reason. So I think that has inflated the numbers.” Right again. Ditto for priests. How many times have we seen false accusations that are purely expressions of vindictiveness?

“I can’t give you the sociological reason,” the mayor said, but, he reasoned, “it far transcends any one type of infraction or complaint. It is a generalized culture we have to address where people use the complaint process for reasons other than a legitimate complaint.” He is thrice right. To anyone who has honestly tracked the issue of priestly sexual abuse, this sounds awfully familiar.

The mayor then said we need to address “something that’s different at DOE than at a lot of other places. And it’s a pretty well-known thing in the education world. Some people inappropriately make complaints for other reasons, not just—I’m not even sure it’s ever about sexual harassment. But it is unfortunately part of the culture.” Grand slam.

De Blasio is on to something real. It may be that educators, given their inflated egos (as compared to sanitation workers, bus drivers, cops, et al.) are more likely to seek revenge against their superiors, or colleagues, if they sense they have been treated unjustly in the workplace. After spending 20 years teaching, ranging from the 2nd grade through graduate school, I can vouch for the plausibility of this observation.

If false accusations in education circles are not an anomaly in real time, they are less an irregularity when considering allegations that took place decades ago. This is the problem with the “look-back” provision of the Child Victims Act that is before the New York State legislature; it allows a one-year window to bring suit against an offender no matter when it occurred. How can we honestly assess past claims, especially given the very real possibility that they are grounded in revenge?

Importantly, the “look-back” provision does not entail young students making claims against an adult teacher: it involves adults making accusations against adults (many of whom are deceased). Regrettably, as we have often seen, old charges made by alleged victims of priests are often fueled by anger against the Catholic Church (usually because of its teachings on marriage and the family), having little or nothing to do with the accused.

This speaks to the merit of de Blasio’s remarks. He is arguing that in too many instances, charges of sexual misconduct are a foil for something more sinister, such as settling old scores. In the case of the Catholic Church, the “pay-back” phenomenon—frequently driven by rapacious lawyers—is all too real.

If the Child Victims Act were to focus exclusively on prospective offenses, few would complain. It is the “look back” provision that is fraught with injustice. It should be excised from the bill being debated in Albany.