On September 7, new documentation found at the Pontifical Biblical Institute was unveiled at the Shoah Museum in Rome. The evidence shows that during the Nazi occupation in Rome, from September 1943 to June 1944, 100 women’s religious orders and 55 men’s religious congregations were responsible for sheltering more than 4,300 persons. Of that number, 3,600 have been identified by name, and 3,200 of them have been “conclusively identified as Jews.”

Many students of this ugly chapter in history are not shocked by the latest batch of documents (there is more to come). It is incontestable that thousands of Jews were hidden from the Nazis in many of the Church’s venues. Israeli diplomat and historian Pinchas Lapide estimated that, overall, the Catholic Church saved between 700,000 and 860,000 Jews. No other religion came close to matching this figure.

Despite this noble record, fair-minded scholars, such as University of Mississippi law professor Ronald Rychlak, have long argued that the Catholic Church has not gotten its due for the yeoman work it did during the Holocaust.

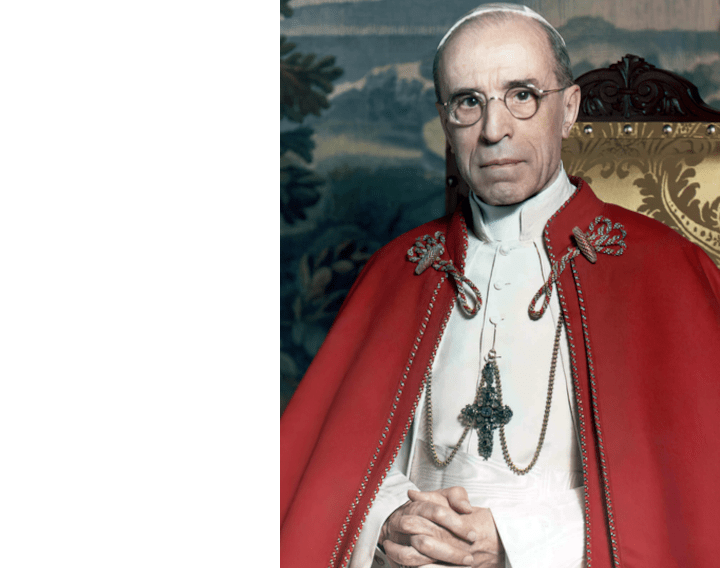

Sir Martin Gilbert, perhaps the foremost historian of the Holocaust, noted that Catholics were among the very first victims of the Nazis and that the Church responded by taking a tough stance against Hitler. The role of Pope Pius XII, he said, can best be assessed by what he did when the Gestapo entered Rome in 1943 to round up Jews. Gilbert wrote that “on his direct authority, [the Catholic Church] immediately dispersed as many Jews as they could.”

Gilbert and I corresponded on this issue, and in 2001 he shared with me something I have never published before now.

After the New York Times praised Pius XII in 1942, the Reich Central Security Office was furious. “In a manner never known before,” the Nazis said, “the Pope has repudiated the National Socialist New European Order… Here he is virtually accusing the German people of injustice towards the Jews and makes himself the mouthpiece of the Jewish war criminals.”

So much for the canard that Pius XII was “Hitler’s Pope.” Nothing could be further from the truth. In fact, Hitler had plans to assassinate the pope.

Even before this time, it was clear that the Catholic Church was doing what it could—without further angering the Nazis—to help Jews. In 1940, Albert Einstein said, “Only the Church stood squarely across the path of Hitler’s campaign for suppressing the truth.” Subsequently, Time magazine and the New York Times also trumpeted the heroics of the Church.

Speaking of the New York Times, what exactly did it have to say about the Holocaust?

It ran only nine editorials criticizing the Nazis in the years 1941, 1942, and 1943 (three each year). Moreover, when the Nazis arrested a cousin of Arthur Sulzberger, the Times chief instructed his Berlin bureau chief to do “nothing.” Sulzberger said he didn’t want to antagonize the Nazis. The cousin, Louis Zinn, was so despondent that after he left prison he hanged himself.

Catholic-Jewish relations are strong today, and we can all be glad that resistance to religious persecution is a widely shared goal in the 21st century. The Holocaust may be unique, but hostility to religious liberty is increasing, both at home and abroad. Vigilance is always in order.