Catholic League president Bill Donohue comments on the never-ending confusion over the meaning of holiday symbols:

Last month a Jewish woman asked a New York Times reporter whether it was discriminatory to deny the display of a menorah in the lobby of her luxury co-op while permitting a Christmas tree. The reply she received was not helpful.

This month a Jewish woman from northern California lost in federal court in her attempt to have a menorah displayed alongside a Christmas tree in a public school that her child attends. Comments made by those on both sides showed how confused they are about this issue.

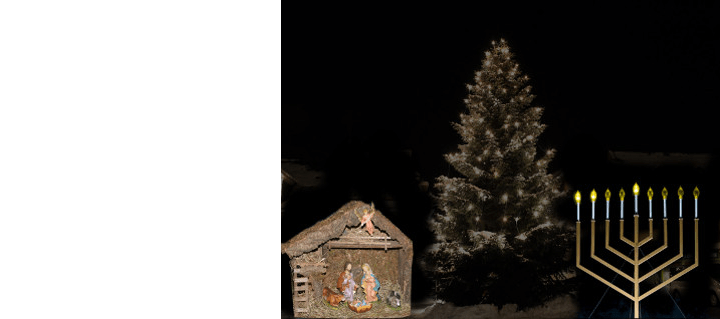

In the New York City case, the Jewish woman was right to complain that for many years the co-op board allowed both the Christmas tree and the menorah. What broke? However, the board chairman was right to say that the menorah is a religious symbol and a Christmas tree is a secular symbol.

Nonetheless, he was wrong to imply that this meant he could not continue the practice of displaying both holiday symbols. There is no law prohibiting him from doing so, which is precisely why he never ran afoul of the law for all the years he allowed both to be displayed.

A reporter for the New York Times was right to say that most apartment buildings elect to display secular symbols during the holidays, thus avoiding controversy over religious symbols. He was wrong, however, to say that the Supreme Court ruled that “a menorah is not a religious symbol when it appears alongside a Christmas tree.” The ruling in question is the 1989 County of Allegheny County v. ACLU decision, and it said no such thing.

That ruling clearly said the menorah was a religious symbol, albeit one that also carried secular meaning. It was decided that it was permissible to display it in the county courthouse because it was erected alongside a Christmas tree, which it properly recognized as a secular symbol. In other words, the menorah never lost its religious significance by putting it next to a secular symbol, but the effect of doing so meant that the entire display could not reasonably be seen as an expression of religion.

In the California case, the woman and her lawyers maintained that the school was showing preferential treatment to Christianity by allowing the display of a Christmas tree but not the menorah. But the former is a secular symbol; a menorah represents a miracle, and as such is properly seen as a religious symbol. The fact that the Christmas tree is associated with a religious holiday—which also happens to be a federal holiday—does not therefore make it a religious symbol anymore than Jack Frost becomes a religious symbol because it, too, is related to Christmas.

It could be argued that the school could have allowed the menorah because it would have been displayed next to a Christmas tree. What complicated this case was the woman’s request to display a huge inflatable menorah; school officials contended that large inflatables are never allowed. She should have taken up their offer to display the menorah in some other part of the school.

Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas has been saying for years that the high court has failed to offer clarity on these matters. He’s right.

At the root of the problem is a militant secularism and intolerance for religious liberty. Christians should welcome the erection of Jewish religious symbols in public places, and Jews should reciprocate; reasonable time limits should be observed.

The fact that this even needs to be said shows how utterly bankrupt the celebration of diversity is: Those who truly believe in diversity would welcome the display of religious symbols, and not try to censor them