| Ronald J. Rychlak

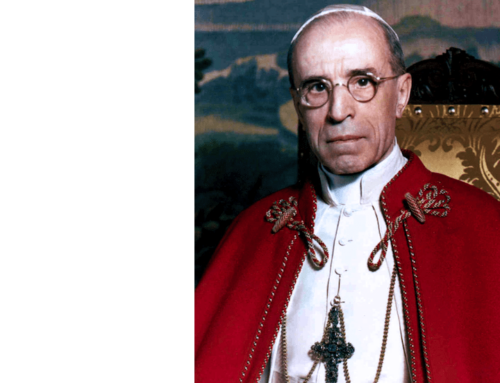

Catalyst, December 1999 John Cornwell’s new book, Hitler’s Pope: The Secret History of Pius XII, turns out to be a deeply flawed attack on Pope John Paul II. That’s right, the final chapter is actually an attack on the current plaintiff. Cornwell is disturbed by John Paul’s “conservative” positions on celibate clergy, women priests, artificial contraception, and abortion. He is especially concerned about the Pope’s opposition to direct political activity by the clergy. Cornwell apparently decided that the easiest way to attack the Pope of today was to go after Pius XII. If he can prove that Pius was flawed, then he establishes that popes can be wrong. If that is the case, then he can argue that John Paul II is wrong about the whole catalogue of teachings that tend to upset many modern Catholics. Cornwell’s thesis is that Eugenio Pacelli–Pope Pius XII–was driven by the desire to concentrate the authority of the Church under a strong, central papacy. Cornwell argues that as Pacelli worked toward that end, he created a situation that was easy for Hitler to exploit. Cornwell denies that Pacelli was a “monster.” In fact, he recognizes that Pacelli “hated” Hitler. His theory, deeply flawed though it may be, is that Hitler exploited Pacelli’s efforts to expand Roman influence. Unfortunately, many reviews, like those in the New York Postand the London Sunday Times, missed that point. They simply reported that “Pius XII helped Adolf Hitler gain power,” as if the two worked together. That is certainly not Cornwell’s point. Some of the mistakes reported in the press are obvious to anyone who read Cornwell’s book. For instance, The Indianapolis News reported that Pius knew of Hitler’s plan for the Final Solution “in 1939 when he first became involved with the German leader.” First of all, the Nazis did not decide on the course of extermination until 1942. Perhaps more telling, this statement is at odds with two things in the book: 1) Cornwell argues that Hitler and the future Pope Pius XII first “became involved” in the early 1930s, and 2) Cornwell expressly notes that Pius XII’s first reliable information concerning extermination of the Jews came in the spring of 1942, not 1939. Similarly, the New York Post reported in a couple of different editions that “Pacelli… met with Hitler several times.” This is not true. The two men never met, and Cornwell does not claim that they did. The most common error by made reviewers was that of accepting Cornwell’s assertions without checking out the facts. On some of these points, the reviewer’s oversight might be forgiven. For instance, Viking Press has marketed this book as having been written by a practicing Catholic who started out to defend Pius XII. One is always reluctant to say what another person’s beliefs are, so reviewers could be forgiven had they simply remained silent about that issue. Instead, the vast majority took delight in calling Cornwell a good, practicing Catholic. Having decided to report on Cornwell’s religious beliefs, the reviewers might have noted that his earlier books were marketed as having been written by a “lapsed Catholic for more than 20 years” and that reviewers said he wrote “with that astringent, cool, jaundiced view of the Vatican that only ex-Catholics familiar with Rome seem to have mastered.” They might also have reported that during the time he was researching this book he described himself as an “agnostic Catholic.” Finally, it might have been worth noting that in a 1993 book he declared that human beings are “morally, psychologically and materially better off without a belief in God.” Instead, they presented only that side of the story that Cornwell and his publisher wanted the public to hear. The Vatican had not yet spoken, so a reviewer might be excused for not knowing that Cornwell lied about being the first person to see certain “secret” files and about the number of hours that he spent researching at the Vatican. When, however, he claimed that a certain letter was a “time bomb” lying in the Vatican archives since 1919, a careful reviewer might have mentioned that it had been fully reprinted and discussed in Germany and the Holy See: Pacelli’s Nunciature between the Great War and the Weimar Republic, by Emma Fattorini (1992). That letter at issue reports on the occupation of the royal palace in Munich by a group of Bolshevik revolutionaries. Pacelli was the nuncio in Munich and a noted opponent of the Bolsheviks. The revolutionaries sprayed his house with gunfire, assaulted him in his car, and invaded his home. The description of the scene in the palace (which was actually written by one of Pacelli’s assistants, not him) included derogatory comments about the Bolsheviks and noted that many of them were Jewish. Cornwell couples the anti-revolutionary statements with the references to Jews and concludes that it reflects “stereotypical anti-Semitic contempt.” That is a logical jump unwarranted by the facts. Even worse, however, is the report in USA Today that Pacelli described Jews (not a specific group of revolutionaries) “as physically and morally repulsive, worthy of suspicion and contempt.” Again, it is a case of the press being particularly anxious to report the worst about the Catholic Church. Cornwell claims that he received special assistance from the Vatican due to earlier writings which were favorable to the Vatican. Many reviewers gleefully reported this and his asserted “moral shock” at what he found in the archives. A simple call to the Vatican would have revealed that he received no special treatment. If the reviewer were suspicious about taking the word of Vatican officials, a quick consultation of Cornwell’s earlier works (or easily-available reviews thereof) would have revealed that he has never been friendly to the Holy See. Cornwell stretched the facts to such a point that any impartial reader should be put on notice. For instance, Cornwell suggests that Pacelli dominated Vatican foreign policy from the time that he was a young prelate. One chapter describes the young Pacelli’s hand in the negotiation of a June 1914 concordat with Serbia (he took the minutes), and leaves the impression that he was responsible for the outbreak of World War I. Certainly Cornwell, who describes Pope Pius XI as “bossy” and “authoritarian,” knows that Pacelli was unable to dominate Vatican policy as Secretary of State, much less as nuncio. Any fair reviewer should have at least questioned this point. Another point that would be a tip-off to any critical reviewer is Cornwell’s handling of the so-called “secret encyclical.” The traditional story (and the evidence suggests that it is little more than that) is that Pius XI was prepared to make a strong anti-Nazi statement, and he commissioned an encyclical to that effect. A draft was prepared, but Pius XI died before he was able to release it. His successor, Pius XII, then buried the draft. One of the problems that most critics of Pius XII have with this theory is that the original draft contained anti-Semitic statements. These critics are reluctant to attribute such sentiments to Pius XI. Cornwell resolved this problem by accusing Pacelli of having written the original draft (or of having overseen the writing) when he was Secretary of State, then burying it when he was Pope. It is really such a stretch that any good reviewer should have questioned it. Instead, most merely took Cornwell at his word and reported that an anti-Semitic paper was written by Pacelli or under his authority. (In actuality, there is no evidence that either Pope ever saw the draft.) Perhaps more startling than anything else is the way reviewers avoided any mention of the last chapter of Cornwell’s book, entitled “Pius XII Redivivus.” In this chapter, it becomes clear that the book is a condemnation of Pope John Paul II’s pontificate, not just that of Pius XII. This chapter also reveals a serious flaw in Cornwell’s understanding of Catholicism, politics, and the papacy of John Paul II. Cornwell argues that John Paul II represents a return to a more “highly centralized, autocratic papacy,” as opposed to a “more diversified Church.” The over-arching theory of the book, remember, is that the centralization of power in Rome took away the political power from local priests and bishops who might have stopped Hitler. Accordingly, Cornwell thinks that John Paul is leading the Church in a very dangerous direction, particularly by preventing clergy from becoming directly involved in political movements, including everything from liberation theology to condom distribution. Cornwell, of course, has to deal with the fact that John Paul II has played a central part in world events, including a pivotal role in the downfall of the Soviet Union. Cornwell’s answer is that John Paul was more “sympathetic to pluralism” early in his pontificate, but that he has retreated into “an intransigently absolutist cast of mind” and has hurt the Church in the process. Cornwell misses the important point that is so well explained in George Weigel’s new biography of John Paul II, Witness to Hope. John Paul’s political impact came about precisely because he did not primarily seek to be political, or to think or speak politically. The pontiff’s contribution to the downfall of Soviet Communism was that he launched an authentic and deep challenge to the lies that made Communistic rule possible. He fought Communism in the same way that Pius XII fought Nazism: not by name-calling but by challenging the intellectual foundation on which it was based. John Paul has recognized the parallels between his efforts and those of Pius XII, perhaps better than anyone else. He, of course, did not have a horrible war to contend with, nor was he threatened with the possibility of Vatican City being invaded, but given those differences, the approach each Pope took was similar. As John Paul has explained: “Anyone who does not limit himself to cheap polemics knows very well what Pius XII thought of the Nazi regime and how much he did to help countless people persecuted by the regime.” The most disappointing thing is that the modern press seems unable to recognize cheap polemics, at least when it comes to the Catholic Church. ___________________________ Ron Rychlak is a Professor of Law and the Associate Dean for Academic Affairs at the University of Mississippi School of Law. His book, Hitler, the War, and the Pope, is scheduled for publication by Genesis Press in June 2000. |

| Copyright © 1997-2011 by Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights. *Material from this website may be reprinted and disseminated with accompanying attribution. |