Catholic League president Bill Donohue comments on Woody Allen’s words of caution in the wake of the Harvey Weinstein scandal:

Jeffrey Katzenberg is right to observe that “There’s a pack of wolves” in Hollywood. They must be gotten. But in the quest for justice, it is important not to proceed at a gallop pace lest we victimize the innocent.

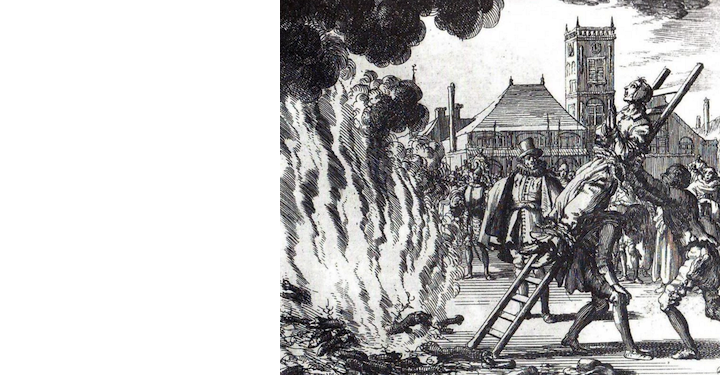

Perhaps the messenger is flawed, but his message is not: Woody Allen is right to warn that in the pursuit of sexual abusers in Hollywood, we need to guard against a witch hunt. We’ve seen this overreaction before, and indeed it is still playing out today in the Catholic Church.

The cover story in Variety is on Harvey Weinstein. Brent Lang and Elizabeth Wagmeister raise an important question. “Will the latest abuse scandal—the worst in modern-day movie business history—force studios to embrace a zero-tolerance environment….?”

Sounds reasonable, but the problem with zero tolerance policies is that they often jettison a strong commitment to the rights of the accused. Moreover, they tend to concentrate as much on minor infractions as they do serious crimes. There are signs that Hollywood is already going down this road, thus making the same mistake as the Catholic Church.

Here is what reporters for the New York Times said in a front-page story on Weinstein on October 17. “A spreadsheet listing men in the media business accused of sexist behaviors ranging from inappropriate flirting to rape surfaced last week and was circulated by email.” There’s the danger.

What is the difference between appropriate and inappropriate flirting? Does this rule apply to women, as well as men? More important, the temptation to lump flirting with rape is disturbing—it can only lead to throwing the book at minor infractions. Indeed, the article noted that “leering” was named as an offense on the spreadsheet listing.

In 2004, the bishops, responding to revelations of sexual abuse in the Boston archdiocese, went into panic mode and adopted a policy of zero tolerance. With the notable exception of Cardinal Avery Dulles, few senior members of the clergy registered any public reservations. To be fair, the media were in overdrive, establishing an hysterical milieu. Still, Dulles should have had more support.

When the John Jay College of Criminal Justice issued its report in 2004 on the issue of priestly sexual abuse, covering the years 1950-2002, it concluded that “inappropriate touching” was the most common offense.

To be sure, this is indefensible, but the problem with “boundary violations” is that they involve, as defined by the charter adopted by the bishops, the “inability to maintain a clear and appropriate interpersonal (physical as well as emotional) distance between two individuals where such a separation is expected and necessary.” Only a lawyer, or a psychologist, is capable of writing such dribble.

What does this mean in real life? In 2012, the ombudsman for the Diocese of Kansas City-St. Joseph explained that a “boundary violation” could mean such things as “sitting too close to a child, seeking time alone with a particular child, or giving gifts or special favors.” This is not a hypothetical case: a priest was suspended from public ministry for a similar offense by the diocese.

The goal of securing a “zero tolerance environment” often leads to another problem: the pursuit of cases from decades ago, and the push to suspend the statute of limitations.

There is a basic civil libertarian principle involved in respecting a statute of limitations: it protects the accused of wrongly being convicted of an offense where witnesses are dead or memories have faded. This is still a problem for the Catholic Church. Consider a story that just broke.

On October 17, 2017, the New York Times ran an article about a Long Island man, now 52, seeking compensation for being molested by a priest, now deceased. The man was 16 when he began sleeping with the priest, and continued doing so for eight years. In other words, when this man was in his mid-twenties, we are expected to believe that he was still a “victim” of sexual abuse.

The Hollywood scandal will continue to grow, and every attempt to punish wrongdoers must be made. But those pursuing justice should not be allowed to run roughshod over the rights of the accused. As we have seen with the Catholic Church, this crusade can easily evolve into a witch hunt.