Catholic League president Bill Donohue holds a Ph.D. in sociology from New York University, and has taught and written on the subject of criminology for many years. He offers the following analysis of the Las Vegas killer:

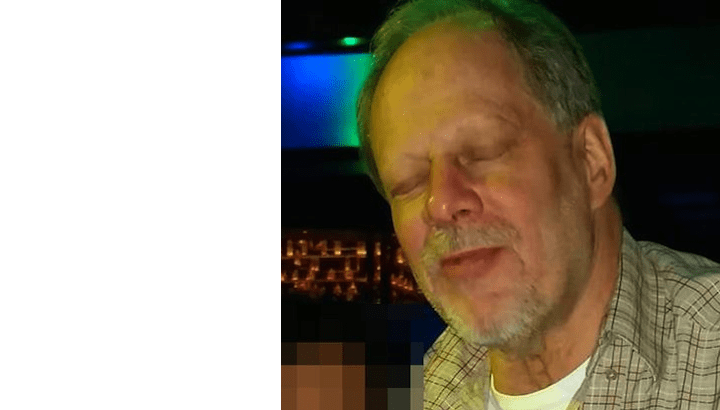

Why did Stephen Paddock murder at least 59 people, wounding well over 500? His rampage was not politically motivated, and he has no history of mental illness. He was a multimillionaire and quite intelligent. Indeed, he worked for Lockheed Martin, the defense contractor, and was an accountant and property manager. But he was socially ill.

To be specific, he was a loner, unable to set anchor in any of his relationships, either with family or friends. That played a huge role in his killing spree, which ended when he killed himself.

Before considering his upbringing and lifestyle, the role that nature may have played cannot be dismissed.

Paddock’s father was a bank robber who was on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted list. More important, he was diagnosed as “psychopathic” and “suicidal.”

“It has been established for some time that genes play a significant role in the makeup of those individuals eventually diagnosed with such conditions as Antisocial Personality Disorder,” writes Dr. George Simon, an expert in this area.

There is no doubt that Paddock was acutely antisocial, and there is much evidence linking that trait to pathological behaviors.

Dr. Samuel E. Samenow is a clinical psychologist and author of Inside the Criminal Mind. He co-authored, with Dr. Samuel Yochelson, the highly influential book, The Criminal Personality. His understanding of mass shooters as loners has much to recommend.

Who are these people? “They are secretive individuals who do not want others to know them. They may be highly intelligent, achieve high grades in school, and even obtain responsible positions.” But their inability to establish bonds is undeniable, and that is critically important to understanding what makes them tick.

Significantly, the loner turned murderer possesses a personality that drives people away from him. “These are not likable individuals,” Samenow says. “No one seems to have known them well. They marginalize themselves, rejecting the world well before the world rejects them.”

Now consider what we know about Paddock. His profile matches up eerily well with Samenow’s observation.

Paddock had no relationship with his gangster father, and was estranged from his brothers. Moreover, he had few, if any, friends. Twice divorced, he had no children. Moreover, he was not in a position to make friends with co-workers: the last time he had a full-time job was 30 years ago.

Paddock never laid anchor anywhere. Growing up, his family moved from Iowa to Tucson to Southern California. His next door Florida neighbor, Donald Judy, said, “Paddock was constantly on the move, carrying a suitcase and driving a rental car,” noting that he “looked like he’d be ready to move at a moment’s notice.”

He certainly got around. He once owned 27 residences in four states, and bragged how he was a “world traveler” and a “professional gambler.” There is no evidence that his world traveling, which was done on cruise ships, ever involved someone else.

Paddock’s recreational pursuits were always solo enterprises. He owned single-engine planes and was a licensed fisherman—a popular solitary sport—in Alaska. His gambling was also a solitary experience. For instance, Paddock did not play the crap table, where gamblers interact. No, he only played video games by himself.

His brother Eric is distraught at his inability to understand Stephen. No matter, his observations about him shed much light on who he was.

Eric said Stephen got bored with flying planes, so he gave it up. It appears that he was looking for some excitement in his lonely life, which explains his gambling preference. “It has to be the right machine with double points,” Eric says, “and there has to be a contest going on. He won a car one time.”

Similarly, Eric notes that Stephen “was a wealthy guy, playing video poker, who went cruising all the time and lived in a hotel room.” He added that he “was at the hotel for four months one time. It was like a second home.” It would be more accurate to say that Stephen never had a home.

Eric recalls that Stephen excelled at sports but never played or joined organized clubs. “He wasn’t a team kind of guy.”

Stephen was not close to any of his brothers, and in the case of Patrick, the two had not seen each other for 20 years. This explains why Patrick did not initially recognize Stephen when his face was shown on TV.

Stephen’s Florida neighbor, Donald Judy, said that the inside of Paddock’s house “looked like a college freshman lived there.” There was no art on the walls, etc, just a bed, two recliners, and one dining chair.

Diane McKay lived next door to Paddock in Reno. “He was weird. Kept to himself. It was like living next door to nothing.” Indeed, “He was just nothing, quiet.”

The local sheriff from Mesquite, Nevada, where Paddock also lived, labeled him “reclusive.” One of Paddock’s neighbors agreed, noting that he was “a real loner.”

“Real loners” are not only unable to commit themselves to others, they are unable to commit themselves to God. So it came as no surprise that Paddock had no strong religious beliefs. It would have been startling to find out otherwise.

It’s all about the “Three Bs”: beliefs, bonds, and boundaries. As I found out when I compared cloistered nuns to Hollywood celebrities on measures of physical and mental health, as well as happiness (see The Catholic Advantage: How Health, Happiness and Heaven Await the Faithful), it is not the nuns who are unhealthy, or who suffer from loneliness, depression, and suicide.

“People who need people are the luckiest people in the world.” This is one of Barbra Streisand’s most famous refrains. She didn’t quite nail it. There is nothing lucky about needing people—it’s a universal appetite. People who have people are the luckiest people in the world. Paddock was not so lucky.

Most loners are not mass murderers, but most murderers are loners. In the case of Paddock, it appears that his antisocial personality, coupled with an acute case of ennui, or sheer boredom with life, found relief by lighting up the sky. Sometimes the mad search for causation can lead us astray; we should not overlook more mundane reasons why the socially ill decide to act out in a violent way.

Sadly, our society seriously devalues religion, celebrates self-absorption, and disrespects boundaries. This is not a recipe for well-being; rather, it is a prescription for mass producing Paddock-like people. We are literally planting the social soil upon which sick men like him feed.