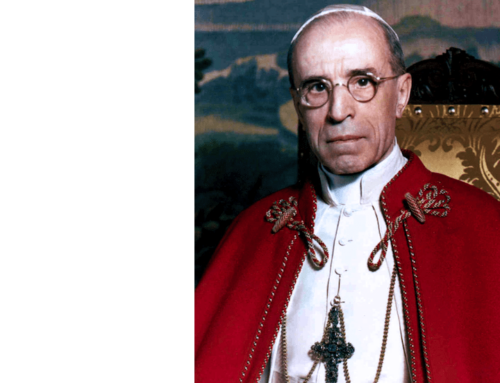

The Pope Pius XII Controversy

A Review-Article By Kenneth D. Whitehead

(The Political Science Reviewer, Volume XXXI, 2002)

I.

One of the most remarkable of phenomena in recent years has been the revival of the controversy over the role of Pope Pius XII during the Second World War, and, specifically, over that pontiff’s stance with regard to Hitler’s effort to exterminate the Jews. First played out over thirty years ago, beginning during the 1960s, the controversy centered on the question of whether Pius XII was culpably “silent” and passive in the face of one of the most monstrous crimes in human history–when his voice as a moral leader and his action as head of the worldwide Catholic Church might possibly have prevented, or at least have seriously hindered–so it is argued–the Nazis in their ghastly plans to implement what they so chillingly called the Final Solution (Endlösung) to a long and widely perceived “Jewish Problem” in Europe.

The controversy over Pope Pius XII has not only been rekindled. It has been extended to include other modern popes and, indeed, the Catholic Church herself as “anti-Semitic.” An unusual number of books and articles has continued to fuel this controversy. Ten of the most recent books on the subject have been selected for evaluation in this review-article.

As the whole world knows, the Nazis succeeded in murdering some six million Jews in gas chambers, mass shootings, and by other means before their lethal activities were finally halted by the allied victory over Nazi Germany in 1945. The controversy which arose around the wartime role of Pius XII, though, did not arise until nearly two decades later, almost five years after the pope’s own death. It was in 1963 that a crude but powerful stage play about the pontiff, The Deputy, [i] became a surprise hit in both Europe and America. Written by a young German playwright, Rolf Hochhuth, the play created a sensation in Berlin and other major European capitals, as it did later in its New York production when it reached these shores early in 1964.

The title of Rolf Hochhuth’s play made reference to the pope as “Christ’s deputy”–or “representative.” The German title was Der Stellvertreter. Catholics do not actually use this term for the pope, of course, but refer to him rather as “the vicar of Christ.” Still, the basic idea of the pope as representing Christ came across; and, in the play, this is intended as high irony, since Pius XII is depicted as a cold, heartless, and narrowly scheming man more concerned about the Vatican’s position and properties than about the fate of Hitler’s victims–more exercised about the allied bombing of Rome than about the murderous atrocities of the Nazis.

The action of the play is principally carried forward by a young Jesuit priest in the Vatican service who learns of the Nazi extermination camps in the East. He is able to bring this information to the attention of the pope himself, but the latter proves unwilling to “speak out” against the gigantic moral evil he has been confronted with. Pius XII is presented as a man “who cannot risk endangering the Holy See…[Besides] only Hitler has the power to save Europe from the Russians.”[ii] Or again: “The chief will not expose himself to danger for the Jews.”[iii]

Hochhuth’s thesis about all this was simple: “A deputy of Christ who sees these things and nonetheless lets reasons of state seal his lips…[is] a criminal” (emphasis added).[iv]What the pope should have done was equally clear to the playwright; in the play, the pope is advised to “warn Hitler that you will compel five hundred million Catholics to make Christian protest if he goes on with these mass killings” (emphasis added).[v] How the pope might possibly “compel” anyone to act merely by speaking out is not specified, but it is intriguing to think that Hochhuth, a non-Catholic, even imagined that the pope might possess such power. Is it possible that some of the subsequent resentment against Pius XII is similarly based on an erroneous belief that a Roman pontiff somehow does have the power to tell Catholics what to think and to compel them to act, but that Pius XII somehow stubbornly refused to do so in order to help the Jews?

The Deputy presented both real and imagined characters on the stage, and purported to be solidly based on historical documentation. The author even included in the published version an extensive discussion of his sources entitled “Sidelights on History,” in which he argued strenuously for his thesis about the culpable silence of Pius XII and concluded that the pope had indeed been a craven fence-sitter. The claimed factual basis for the play, however, did not prevent Hochhuth from including historical distortions which went far beyond any legitimate dramatic needs, and not a few outright falsehoods, such as presenting Pius XII as ordering Vatican-owned Hungarian railroad stocks to be sold because the Soviets were about to enter Hungary; or as being in direct communication (in confidence) with Adolf Hitler regarding the progress of the war.[vi] Pius XII never met Hitler in person, nor was he at any time ever in direct contact with him beyond the exchange of diplomatic correspondence.

The level of Rolf Hochhuth’s real understanding of the wartime situation may perhaps also be gauged by his assertion that by October, 1943, “there was no longer any reason for the Vatican to still be afraid of Hitler.”[vii] In actual fact, of course, the Germans had just occupied Rome the month before, following the fall of Mussolini and Italy’s surrender, and so the possible immediate danger to the headquarters of the Church was greater than ever. The Germans would keep the city in a tight grip for eight more months until it was liberated by the allies on June 4, 1944.

Yet for all of its inaccuracies and even crudities, The Deputy was a huge success. It was translated into more than twenty languages and, virtually by itself, launched the original Pius XII controversy. In his review of the play’s New York staging, Walter Kerr, then dean of American drama critics, expressed surprise that “so flaccid, monotonous, and unsubtle a play” should have had such an effect. Yet he probably spoke for many average viewers and newspaper readers when he observed that The Deputy had nevertheless shocked people “into the realization that a question exists which has not been answered…What were Pius’s motives for remaining silent? Were they–could any conceivable combination of motives possibly be–adequate to account for what he did not do?”[viii]

Thus was posed by a drama critic what almost instantly came to be believed by the public at large to be the essential question as far as the wartime role of Pope Pius XII was concerned. It has pretty much remained the essential question in the public mind ever since. Once the question of why the pope had not spoken out had been effectively posed in such plain and blunt language, that he most certainly should have spoken out seemed perfectly obvious to most people; that there might possibly be any valid reasons why he should not have spoken out simply seemed counter-intuitive to many, as it apparently did to drama critic Walter Kerr (himself a prominent Catholic, as it happened).

Few probably ever stopped to consider whether there might have been any special circumstances related to wartime conditions or to the Vatican’s international position and special history which might have militated against the pope’s speaking out. This viewpoint is especially predominant today when we are so accustomed to having a Pope John Paul II constantly speaking out on moral questions such as war, economic exploitation, bio-technology, legalized abortion, euthanasia, and the like.

The fact that this viewpoint predominates today tends to give the critics of Pius XII somewhat of an advantage, since they are generally able to gain immediate broad acceptance of their assertions about what the pope and the Church should have done during World War II. The defenders of Pius XII, on the other hand, generally have to scramble even to get a public hearing, much less persuade public opinion in their favor; more than that, they are too often apt to be dismissed as mere knee-jerk Catholic apologists.

Almost immediately following the controversy stirred up by The Deputy, an extensive controversial literature, both scholarly and popular, about Pope Pius XII and his wartime role grew up. This literature included questions not only about why he was silent about the Holocaust against the Jews, but about whether, in fact, he was all that silent; about what his policies and actions were with regard to the Jews and other war victims–in other words, what, specifically, did he do, if anything, for Jews and other war victims? Other pertinent questions included what his attitudes and aims were towards the Nazis, the Communists, and the Western democracies. Did he, as is still often implied and sometimes even plainly stated, “collaborate” with the Nazis because of his fear of Communism and Soviet expansionism? Finally, what credit or responsibility belonged to the pope for actions taken, or not taken, by Catholics throughout Europe in favor of the Jews?

Still other questions arose as well, some of them predicated on the assumption simply regarded as proven fact that the pope had indeed been culpably silent and passive in the face of the Nazi onslaught: was the pope himself perhaps an anti-Semite? Anti-Semitism was an attitude and prejudice unfortunately deeply rooted in European history, after all, and some Catholics undeniably shared it. Did Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli, the future Pope Pius XII, as papal Secretary of State under Pope Pius XI, pursuing his penchant for diplomatic arrangements between governments, perhaps even help enable the Nazis to seize power in Germany by negotiating the Vatican Concordat that was concluded with Nazi Germany in 1933?

All of these questions (and a few more!) are pretty extensively if not exhaustively covered in the ten books under review here, all of them published within the past four years. Eight of these authors deal specifically with Pius XII (or the Catholic Church), the war, and the Holocaust against the Jews (Blet, Cornwell, Marchione, McInerny, Phayer, Sánchez, and Zuccotti); another one deals more generally with papal attitudes towards and treatment of the Jews which presumably contributed to the eventual perceived failure of Pius XII in World War II (Kertzer); and a final one deals with what the author calls “papal sin” in general, though he includes a chapter on Pius XII and the Holocaust (Wills).

Five of these authors take a more or less frank anti-Pius (or anti-Church) view (Cornwell, Kertzer, Phayer, Wills, and Zuccotti). Four of them expressly set out to defend the pontiff (Blet, Marchione, McInerny, and Rychlak). One of them declares that his aim is to remain above the fray and simply evaluate some of the arguments, pro and con (Sánchez).

It is perhaps not surprising that the anti-Pius books here should be the ones on the best-seller lists, the ones that have attracted the most public attention. These anti-Pius books too are the ones published by mainstream New York publishers such as Doubleday and Knopf or by university presses, and they are also the ones most likely to be found on public library or bookstore shelves. All four of the pro-Pius books, by contrast, are published by small religious publishers with much less access to bookstore sales and a wide readership. Nor do the pro-Pius books appear to have been reviewed either as widely or as often as the anti-Pius ones; so it seems to be a simple fact that the latter have largely shaped the debate to date. Even so, for reasons that I will try to make clear as I go along, I think the pro-Pius books still have much the better of the argument. Yet in view of the importance of the controversy, all of the books deserve a close look.

What still remains more than a little surprising, though, is that we should have all of these books on this subject more than fifty years after the events they deal with. We might have thought that the Pius XII question would have been thoroughly aired and settled by the plethora of books and articles that appeared on the subject in the 1960s and after, during the initial Pius XII controversy set off by The Deputy. Actually, there has all along been a fairly steady trickle of books and articles down through the years from then until now, and thus there now does exist a truly vast literature in a number of languages on Pius XII and the Holocaust, much of it in relatively obscure scholarly journals, though, and thus not always in the forefront of public attention, but nevertheless there. The most recent books, though, have now served to re-ignite the controversy and to attract greater public attention to the Pius XII question once again.

Even so, there is not all that much that is new. Books such as Guenter Lewy’s The Catholic Church and Nazi Germany[ix] and Saul Friedländer’s Pius XII and the Third Reich[x] covered much of the essential material available at the time, ending up with negative views about the wartime role of Pius XII, though couched in scholarly terms. In defense of the pope, Pinchas Lapide, an Israeli diplomat, who had been present at the liberation of some of the Jews interned in Italy, and who admired Pope Pius XII, wrote his The Last Three Popes and the Jews,[xi] in part to counter the claims of authors critical of the pope. Similarly, Michael O’Carroll, C.S.Sp., in his Pius XII: Greatness Dishonored: A Documented Study,[xii] attempted to defend the pope by placing his words and actions in a different perspective than the one taken for granted following The Deputy. These and other books and articles, pro and con, have covered almost every imaginable aspect of the subject.

So persistent was the controversy in the 1960s, however, that Pope Paul VI, who as Archbishop G.B. Montini had been one of Pius XII’s principal collaborators during the war years–and who himself published a brief defense of Pius XII that appeared in the week following his own election as Pope Paul VI on June 23, 1963[xiii]–waived the strict time limits (45 years) governing access to the archives of the Vatican Secretariat of State, and assigned three Jesuit historians, a Frenchman, a German, and an Italian, to search the archives and prepare for publication all the documents pertaining to the Vatican’s activity during the war. The idea was to provide solid documentation for the role of the pope and the Vatican during that conflict. The three Jesuit historians assigned to this work were later joined by a fourth, the American Jesuit historian, Father Robert A. Graham, S.J., who wrote and published prolifically on the subject in subsequent years.

The results of the intense labors of these four Jesuits, completed in 1981, amounted to twelve volumes published under the title Actes et Documents du Saint-Siège relatifs à la Seconde Guerre mondiale (“Acts and Documents of the Holy See relative to the Second World War”; abbreviation ADSS).[xiv] With a narrative written in French, but with the collected Vatican documents retained in their original French, German, Italian, Latin, Spanish, or English, this important collection resembled such commonly consulted collections of documents as, for example, the Foreign Relations of the United Statesseries. In a different climate, the collection might have had the potential to settle many if not most of the questions surrounding Pope Pius XII and his wartime role.

Nothing of the kind ensued, however. Most of the works devoted to or mentioning Pius XII tended to continue along the same anti- or pro-Pius lines as before. The ADSS collection did not seem to be all that prominently consulted or cited anyway–as can even be seen in the bibliographies of some of the books under review here. So disappointed was the Vatican in noting the little effect the ADSS collection seemed to be having that the remaining sole survivor of the original four-Jesuit research team, Father Pierre Blet, S.J., decided to prepare a concise one-volume summary of the contents of most of the ADSS collection; this summary volume was published in 1997 in French and in English translation in 1999; it is one of the books under review here (Blet).

Also in October, 1999, the Vatican Commission for Religious Relations with the Jews reached agreement with the International Jewish Committee for Interreligious Consultations, an umbrella organization of Jewish groups, to appoint a special International Catholic-Jewish Historical Commission, consisting of six historians, three Catholic and three Jewish, to examine critically the twelve volumes in the ADSS collection.

This initiative grew out of Vatican disappointment with Jewish reaction to a 1998 Catholic Church statement entitled We Remember: A Reflection on the “Shoah” (or “Holocaust”).[xv] The Church had issued this statement as a kind of “apology” for any Church or Catholic sins, whether of omission or commission, against the Jews. The reaction of some Jewish readers, however, proved to be distinctly cool; the Church’s attempt at an “apology” did not go nearly far enough, in their view.

For example, the highly respected Commentary magazine published a critique of the We Remember document by the historian Robert S. Wistrich of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. While agreeing that “one cannot but commend both its tone and its basic aims,” Professor Wistrich nevertheless found it “not especially flattering to the Church’s declared aspirations.” Briefly surveying some of the same questions about the behavior of the pope and the Church during the Holocaust that are covered at greater length in most of the books under review here, he essentially endorsed the anti-Pius viewpoint on most of these questions and faulted the We Remember document for attempting to hold that the Church was “blameless during the Shoah.” He thought a more “honest reckoning with the past” was called for, though his tone remained moderate and civil. Moreover, Commentary magazine generously gave considerable space in a subsequent issue to rather extensive rebuttals by Catholic defenders of the pope, among others.[xvi]

Thus, in spite of the Church’s attempt at an “apology,” the Pius XII controversy simply seemed to be heating up even more. The appointment of a joint International Catholic-Jewish Historical Commission to examine some of the relevant documents seemed a logical next step to help cool it down. The idea seemed to be that a mixed group composed of both Catholic and Jewish scholars, most or all of whom had published studies on the Holocaust, could reach a consensus on at least some aspects of the role which the pope and the Catholic Church had played in the war–a consensus that could then serve to lower some of the decibels in the Pius XII controversy.

One year later, on October 25, 2000, this joint Historical Commission issued a preliminary report, “The Vatican and the Holocaust,”[xvii] which contained more questions than conclusions, 47 of them to be exact. The report containing these questions was submitted to Rome with a request for greater access to archival documents. “Scrutiny of these [published] documents does not put to rest significant questions about the role of the Vatican during the Holocaust,” the report said. “No serious historian could accept that the published, edited volumes could put us at the end of the story.”

Nearly a year after that, in July, 2001, the six Catholic and Jewish historians wrote to Cardinal Walter Kasper, the new head of the Vatican Commission for Religious Relations with the Jews (who had asked them for a final report), saying that in order to continue working together they needed “access in some reasonable manner” to the Vatican’s unpublished archival material.[xviii] Except for the ADSS volumes produced as a result of Pope Paul VI’s special dispensation, of course, the Vatican archives were open to scholars only up to the year 1922. It was explained to the six historians that the archival materials for the war years consists of more than three million pages still uncatalogued; there was no easy–or perhaps even possible–way the historians’ request could be granted, at least for the moment.

The six historians were obviously at an impasse with the Church, and, shortly after that, their work was suspended and the group broke up, amid recriminations on all sides. It appeared that Paul VI’s hope that opening up the documents to the extent that he did might help settle the controversy, along with the sixteen years of work put in by the four Jesuit historians, had gone for naught.

Father Peter Gumpel, S.J., the relator (or “judge”) of the cause of Pope Pius XII for sainthood, issued a very sharp statement almost unprecedented for a Vatican official accusing “some–not all–of the Jewish component of the group” with publicly spreading “the suspicion that the Holy See was trying to conceal documents that, in its judgment, would have been compromising. These persons then repeatedly leaked distorted and tendentious news,” Father Gumpel charged, “communicating it to the international press.” They were, in his view, “culpable of irresponsible behavior.”[xix]

Some Jewish leaders, perhaps understandably, responded in kind to this blast.[xx] The joint Catholic-Jewish effort to resolve the Pius XII controversy, or at least lower the decibels, had thus instead only served to raise the latter, and for the time being at least, was at an end.

In spite of this disappointment, however, the Vatican announced in February, 2002, that it would soon be releasing Vatican-German relations documents for the years 1922-1939.[xxi] This would seem to represent an effort on the part of the Church to respond to accusations that evidence from the wartime years was being “concealed.”

At the same time that the Vatican Commission for Religious Relations was laboring to set up the joint Catholic-Jewish panel of historians, another and much broader public controversy over Pius XII was just about to break out, one that would no longer be characterized by the civility of the Commentary intervention. This major escalation of the controversy began in earnest when Vanity Fair magazine, in its issue of October, 1999, published a preview and excerpt from the then forthcoming book of John Cornwell,Hitler’s Pope: The Secret History of Pius XII. This, of course, is one of the books under review here, and it attracted a great deal of attention from the very start; it quickly became something of a best seller; it was quite widely reviewed, and, very soon, its author also was out on the talk-show circuit. At one stroke, we were back in the middle of the Pius XII controversy in a manner reminiscent of the days of The Deputy. The excerpt from the book published in Vanity Fair was typical–and sensational: Long buried Vatican files reveal a new and shocking indictment of World War II’s Pope Pius XII: that in the pursuit of absolute power, he helped Hitler destroy German Catholic political opposition, betrayed the Jews of Europe, and sealed a deeply cynical pact with a 20th-century devil.

This sensational introduction in the magazine reflected only too accurately both the tone and content of John Cornwell’s book. Supposedly a work of serious history, the book actually lent itself all too easily to the Vanity Fair style of treatment. None of the statements just quoted from it above are true, of course:

m There was no previously unknown and “shocking” information about Pope Pius XII found in “long-buried Vatican files”; virtually everything in Cornwell’s book had previously appeared in the extensive published literature concerning Pius XII and the wartime period.

m Eugenio Pacelli did not “help” Hitler destroy German Catholic political opposition; the Nazis did away with all German political parties except their own within months of coming to power.

m Nor did the pope in any way “betray” the Jews. The Concordat which the then Cardinal Pacelli negotiated with the Nazi government was not a “deeply cynical pact,” but was the standard kind of agreement the Vatican had negotiated with numerous governments spelling out the legal status and rights of the Catholic Church in their countries.

While the Vanity Fair lead-in to Cornwell’s book did not come from the pages of the book itself, the author nevertheless readily accepted this kind of sensational publicity for what he had written. We shall have to look at the book itself in its proper place; but before the book even appeared, the accusations against Pius XII had already been very effectively broadcast by this kind of publicity. The Pius XII controversy was no longer–if it ever had been–merely a debate or dispute among historians or scholars with differing views about the same historical record. It was already, and irretrievably, a public and media event, in which the charges and counter-charges made by the accusers and defenders of the pontiff, respectively, were as likely to appear on a daytime talk show or on the evening news as in a book or periodical reaching a only limited number of people. As we look at the books under review here, we are going to have to remember that they are part of this much broader and on-going public controversy.

Moreover, some of the implications and effects of this broader public controversy themselves go beyond just the words and acts of Pius XII during the war with regard to the Jews. In the course of an excellent review-article in The Weekly Standard concerning some of the very same books being reviewed here, for example, Rabbi David G. Dalin noted the striking fact that some of the bitterest attacks on Pius XII have been made by disaffected Catholics. These include, especially, the books by ex-seminarians John Cornwell and Garry Wills reviewed here, as well as another book, not reviewed here, ex-priest James Carroll’s Constantine’s Sword.[xxii] Rabbi Dalin noted, pertinently, that:

Almost none of the books about Pius XII and the Holocaust is actually about Pius XII and the Holocaust. Their real topic proves to be an intra-Catholic argument about the direction of the Church today, with the Holocaust simply the biggest club available for liberal Catholics to use against traditionalists.[xxiii]

This is not true of all of the books critical of Pius XII, of course; but it is a prominent and significant and, for some, perhaps surprising, element in the present revived Pius XII controversy. Rabbi Dalin believes it “disparages the testimony of Holocaust survivors and thins out, by spreading to inappropriate figures, the condemnation that belongs to Hitler and the Nazis.” He objects to what he calls an “attempt to usurp the Holocaust and use it for partisan purposes.”

However, it is not the case that dissident Catholics are the only ones prepared to use the Pius XII controversy for partisan purposes. In yet another lengthy review-article in The New Republic of some of the same books under review here (along with some others), Daniel Jonah Goldhagen, author of the very widely noticed 1996 book Hitler’s Willing Executioners,[xxiv] launched a generalized attack not only on Pius XII, but on the Catholic Church as a whole as a thoroughly anti-Semitic institution “at its core.”[xxv] In his earlier book, Goldhagen found it possible to fix collective guilt upon the German people generally for the crimes of Hitler and the Nazis; in his New Republic article, he makes the same charge as far as Catholics and the Catholic Church are concerned, charging Christianity and, specifically, the Catholic Church with “the main responsibility” for the anti-Semitism which issued in the Holocaust. Scorning today’s usual attempts at polite “ecumenism,” which even many critics of Pius XII often still try to maintain, at least in words (and just as the defenders of Pius XII are careful to dissociate themselves from any hint of possible anti-Semitism), Goldhagen bluntly charges the Church with harboring anti-Semitism “as an integral part of its doctrine, its theology, and its liturgy. It did so,” he claims, “with the divine justification of the Christian Bible that Jews were ‘Christ killers,’ minions of the Devil.” Noted in his article is an announcement that these claims will be thoroughly elaborated upon by him in a forthcoming book with the title A Moral Reckoning: The Catholic Church During the Holocaust and Today. It looks to be quite some book!

But already, at one stroke, with this New Republic article, the on-going and already very public controversy over Pius XII has been broadened and extended to include the whole Catholic Church, including the Church today. Daniel Jonah Goldhagen is not going to pull any punches, but is going to lay them on. It is more than likely, of course, that this new escalation of the Pius XII controversy will have significant fall-out, perhaps for years to come: it has been launched by a supposedly mainstream political journal, and the book setting it forth will issue from one of America’s most prestigious publishers.

Those who hoped for a settlement of the Pius XII question, or at least a moderation of it, are surely going to be disappointed; henceforth we will not only have charges of anti-Semitism bandied about; we may well now have charges of anti-Catholicism as well.

And it should be underlined that Goldhagen apparently bases his attack on Catholics and the Catholic Church very largely on some of the very same books that are under review here: if these books are correct and solidly based, then the Goldhagen thesis should be enhanced accordingly. By the same token, if these books are deficient, then his position would seem to suffer correspondingly.

As encountered in his article, his historical references are so generalized and careless and imprecise–and even inaccurate–while his tone is so overwrought and exaggerated–that one actually hesitates to say how bad his article really is; one hesitates for fear of seeming to share in his intemperance! It may even be unfair that some of the books he is supposedly reviewing–and we too are reviewing–are being made to bear the burden of possible support for his extremism.

In the light of this dramatic escalation of the Pius XII controversy, though, it is doubly important that we look very carefully at the books under review here; the importance of reviewing these particular books could not have been more resoundingly vindicated by this latest development in the controversy over Pius XII and the Holocaust.

Mostly on the basis of the “facts” supposedly established by the books critical of Pius XII utilized by Goldhagen, the publisher of The New Republic has felt able to declare to the world at large that Pope Pius XII was simply an “evil man.”[xxvi] This kind of denigration of the World War II pontiff is unfortunately not uncommon.

At the same time, in February, 2002, the Berlin International Film Festival gave its prestigious award to a new film, entitled simply Amen, by the Greek-born French film director Constantin Costa-Gavras; it is a film about a German SS officer who tells a Catholic priest about the Nazi extermination program going forward in the East; when the priest gets this information to the pope, however, the latter refuses to do anything about it.[xxvii]

This new film is directly based, of course, on Rolf Hochhuth’s The Deputy. That it has been produced and brought out just at this time, however, makes it one more important element in the revived Pius XII controversy; no doubt the film will spread the received opinion on the culpable papal silence and passivity in the face of gigantic evil even more widely than it has been spread already.

II.

All of the books we are reviewing here on the general topic of Pius XII and the Holocaust deal with pretty much the same set of facts, most of them long on the record in the voluminous Pius XII literature. Contrary to the opinion of the members of the now sadly defunct International Catholic-Jewish Historical Commission, it is really unlikely that many (or any) startling new revelations will come to light when the Vatican finally opens its archives completely for the war years.

It is difficult to understand, in fact, why this mixed Commission of six historians could not have produced a final report on what the published ADSS collection does show about the controversy, recognizing that their conclusions certainly could later be modified by subsequent new evidence; the writing of history, after all, is almost always in need of revision as perspectives change and as new facts are turned up. At the same time, historians almost always have to depend on “incomplete” sources. To claim that the picture can only be filled in completely when the Vatican finally gets around to divulging what it has allegedly been holding back is neither responsible nor persuasive.

What we have in the ten books under review here is treatment of the same basic body of facts from different perspectives, pro and con. Since the anti-Pius authors believe that the pontiff should have spoken out and acted more vigorously to help the Jews, they naturally tend to concentrate on those instances when he failed to do so, in their view, and to downplay or explain away those instances that might call their thesis into question. As Rabbi David G. Dalin, not unfairly, describes this approach: “It requires…that favorable evidence be read in the worst light and treated to the strictest test, while unfavorable evidence is read in the best light…”[xxviii]

Somewhat the same approach is encountered among the pro-Pius authors: they too understandably try put the best construction possible on the words and actions of Pius XII which support their view, and, where they can, they too tend to downplay those things that tell against their view. Since the point of view of the pope’s defenders is predominantly reactive, however, they are generally less likely to downplay or ignore facts and arguments which do not seem to favor their position because they are, after all, precisely engaged in answering the charges made against the pope; they have to recognize them in order to answer them.

By and large, the authors on both sides talk past one another. With three exceptions–Ralph McInerny’s animadversions on the books by Cornwell and Wills, Ronald Rychlak’s “Epilogue” specifically devoted to analyzing critically John Cornwell’s book, and José Sánchez’s effort to evaluate the literature on the controversy generally–these books were mostly written independently of each other, even though they are generally based on the same set of facts. We therefore need to look at each one individually.

But before we do so, we also need to consider several general questions about the wartime role and situation of Pope Pius XII as these appear to the present reviewer, after having plowed through all of these ten books.

My overall impression is that all of the authors, in one degree or another, are focused so narrowly on the pope and the Jews that they sometimes fail to see and appreciate the larger picture concerning what was going on, namely, that there was a war going on! It was a total war too, and one that was being conducted on a worldwide scale; and for those who found themselves inside the territories controlled by the Axis–and this included the Vatican for most of the war–wartime conditions necessarily limited their ability to function in so many different ways that it cannot be assumed that they were entirely free agents in any respect.

As for the pope and the Vatican Secretariat of State, responsible for managing the affairs of a worldwide Church under these difficult conditions–and with a small staff of only about thirty people in all, including clerical help (Sánchez, 44; Zuccotti, 90)–it has to be realized that they at all times and constantly had other and pressing concerns besides just following and reacting to what was happening to the Jews. Indeed, one of the six historians on the defunct joint Catholic-Jewish Commission, Eva Fleischner, whose work judging from mentions in bibliographies has been quite narrowly focused on the Holocaust, was able to observe with refreshing candor in this regard that the ADSS collection revealed to her a Vatican “bombarded on every side about every conceivable human problem. The question of the Jews was there, but was not paramount. In that respect, I understand much better than I did to begin with.”[xxix]

Speaking as a former practicing diplomat myself, I sometimes found the apparent expectations of some of these authors concerning what the Church actors in this drama could or should have been doing in the actual situations described to be simply unreal.

Another assumption of most of these authors, especially those in the anti-Pius camp, is that Pius XII was necessarily free in the conditions of war and occupation that obtained to speak out or to make public protests in the way that they think he should have, looking at things from their post-Holocaust perspective. Both before and during the war, the 107-odd acre Vatican City was entirely surrounded by a hostile Fascist regime in Italy, which, not incidentally, also controlled the Vatican’s water, electricity, food supply, mail delivery, garbage removal, and, indeed, its very physical accessibility by anybody. John Cornwell admits that Mussolini could have taken over the Vatican at any time (Cornwell, 236)–if sufficiently provoked (or prodded by Hitler). The Italian Foreign Minister, Count Galeazzo Ciano, recorded in his diary in March, 1940, that Mussolini seriously considered “liquidating” the Vatican (Rychlak, 140); for the pope it was not an imaginary threat but an active possibility for most of the war.

From September, 1943, to June, 1944, Rome was under harsh German military occupation, and it was during this period that Hitler seriously considered occupying the Vatican and abducting the pope, as a number of sources attest and as some of our authors do not fail to record (Cornwell, 313-315; Phayer, 100; Rychlak, 264-266; Zuccotti, 315-316). Nor, in the Vatican’s experience, was this any imaginary threat, either: both the French Revolution and Napoleon had done precisely that in the cases of Pope Pius VI and Pope Pius VII, having abducted both popes by military force and transported them beyond the Alps (Pius VI died in exile in France). For the pope there were obviously troubling precedents for what Hitler was reported to be considering–and such reports did come to him. Margherita Marchione describes yet another Nazi plan to attack the Vatican using captured Italian uniforms, a plan which came to light only in 1998, as Milan’s Il Giornale reported (Marchione, 72-73).

Throughout his tenure as German Ambassador to the Vatican, Ernst von Weizsäcker, “constantly worried that Hitler would order an invasion of the Vatican” (Rychlak, 207). His dealings with the Vatican and his reports back to Berlin reflected that fear. There was never a time before June 4, 1944, when the Allies liberated Rome, that Pius XII and his Vatican colleagues did not have to fear a possible Vatican takeover by armed force.

Nor was this simply a matter of fear for their personal safety. Pius XII more than once gave proof of his personal courage; but he and his colleagues had serious responsibilities at the head of a worldwide Church with members in all the belligerent countries not to put themselves at undue risk if they could help it. As the war progressed, and Adolf Hitler proved himself capable of anything, anyone in their situation would have had to weigh carefully at all times just what they could or could not do or say. The idea that Hitler would have allowed any effective opposition to his obsessive plans is a very, very large assumption.

Several of our authors even recognize that Fascist or Nazi threats against the Vatican were considerably more than theoretical. “As a demonstration of their power,” writes Susan Zuccotti, not otherwise favorable to Pius XII, “they maintained continual harassment. Fascist thugs beat up newspaper vendors of L’Osservatore Romano in the streets of Rome in 1940, when the journal was still printing war reports that included news of Italian defeats. The Vatican radio was regularly jammed. Italian and German censors consistently interrupted and read diplomatic communications of the Holy See (Zuccotti, 316; see also Blet, 44; Cornwell, 243-244; Rychlak, 39). Under these circumstances, perhaps the wonder is that the pope was able to say as much as he did during the war.

Another quite unproven assumption that seems to be taken for granted on the anti-Pius side is the notion that if the pope had only spoken out, his words would necessarily have been heeded, if not by the Axis governments and their satellites, at least by the Catholic peoples of Europe, who presumably could or would then have opposed what their governments were doing. This assumption seems both unrealistic and unlikely, quite apart from the penalties that citizens in the Axis countries and their satellites would have incurred for opposing their governments.

As for the Axis governments, the Concordats which the Vatican had concluded with both Hitler and Mussolini began to be violated almost as soon as they were concluded. Ralph McInerny counts no less than 34 notes of protest to the Nazi government that went unheeded between 1933 and 1937; these blatant violations, indeed, were among the things that led up to the encyclical of Pope Pius XI against the Nazis, Mit Brennender Sorge (“With Burning Anxiety”), that was issued in the latter year. By 1939, 55 protest notes documenting violations had been lodged with the German government, most of which simply went unanswered (McInerny, 26 & 30). The Vatican had long experience of its protests going unheeded.

By the time the war came, there was a firmly established pattern of Axis rejection of Vatican protests; on any given occasion, the pope had to expect that, in all likelihood, his words would not be heeded. As the war progressed, this unhappy reality was made quite explicit by the Germans. For example, by June, 1942–after numerous appeals had already been made specifically on behalf of Jews–the Vatican Ambassador to Germany, Cesare Orsenigo, reported to G.B. Montini, the future Pope Paul VI, who had just lodged yet one more appeal on behalf of a Jewish couple, as follows: “I regret that, in addition, I must add that these interventions are not only useless, but they are even badly received; as a result, the authorities show themselves unfavorable to other…cases” (Blet, 148). Perhaps the surprising thing, again, is that the Vatican continued to lodge protests anyway under such conditions.

Another writer, Father Vincent A. Lapomarda, S.J., observes that, according to volumes 6, 8, 9, and 10 of the twelve-volume ADSS collection, the Vatican intervened some 1500 times on behalf of victims of the Nazis.[xxx]

Vatican efforts to influence the Italian government were equally assiduous but usually proved equally futile as long as the Fascists were at the height of their power. In a discussion of Vatican protests against the Italian racial laws in which Susan Zuccotti really seems to be trying to show that the Vatican was only interested in Jews who had converted to Catholicism, she also brings out, no doubt inadvertently, just how little influence Vatican protests really had on the Italian Fascist government. “The answers were almost always negative,” Zuccotti writes. “…Mussolini granted no modifications” (Zuccotti, 64-65).

The whole question of special Church emphasis on assistance to Jewish converts to Catholicism, by the way, which the anti-Pius writers generally take as one more piece of evidence that Pius XII had no interest in or concern for the Jews as such, surely needs to be understood in the light of the fact that the Church had a legal right–and responsibility–under the Concordats to plead for these particular victims, whereas the totalitarian governments did not consider or recognize that the Church had any standing to intervene on behalf of the Jews. More than that, the Jewish agencies in the field provided no assistance to these Jewish converts to Christianity; the Church was their only possible source of support (Blet, 147; McInerny, 55).

As for the idea that public protests by the pope or the Church might have aroused Europe’s Catholic populations to oppose the anti-Jewish measures being carried out by their governments, this idea seems to assume that whenever a pope or a Catholic bishop says something, Catholics will then automatically fall into line to carry out the Church’s “orders.” This view recalls Rolf Hochhuth’s idea that Pius XII could somehow “compel” Catholics to act; it is based on a serious misunderstanding of how Church authority works.

We need only think, for example, of the many strong and repeated statements that Pope John Paul II and the U.S. Catholic bishops have regularly made against legalized abortion in the United States–and then gauge the effect these statements have had on, say, such pro-abortion senators identifying themselves as Catholics as Edward M. Kennedy or John Kerry of Massachusetts; or, for that matter, on the large majorities of Catholic voters in Massachusetts, who put and keep such politicians in office in spite of what the Church teaches.

It is exceedingly naïve to imagine that Catholic prelates can simply issue “orders” to their flocks with the expectation that what they say will be carried out; yet it seems to be a common assumption among many who fault Pius XII for not having issued the proper “orders.”

The sad fact is that most German Catholics, like most Germans, especially in the beginning, were attracted to Hitler and the Nazis as the putative saviors of their country. Most Germans had opposed the Versailles Treaty after World War I as unjust to Germany, and most thought Hitler was justified in seeking its revision. As everybody knows, the Nazis came to power by completely legal and constitutional means, and only afterwards dismantled the democratic institutions of the Weimar Republic and instituted totalitarian rule. Under their regime, too, Germany went from six million unemployed in 1933 to full employment by the time the war came,[xxxi] and, until Hitler brought ruin on the country by making war, many Germans viewed him not too differently from the way the Americans of the same years viewed Franklin D. Roosevelt.

That the Germans should have reacted to the ugly and atrocious crimes that the Nazis began to perpetrate virtually as soon as they gained power is clear enough to us in hindsight; but the fact is that the Germans did not generally so react; they followed Hitler into what became the catastrophe of the war; and it seems quite unrealistic to imagine that anything that the popes might have said or done beyond what they did say and do would under the circumstances have had much influence on German Catholics in this regard.

Yet Michael Phayer thinks that “because Church authorities left Catholics in moral ambiguity by not speaking out, the great majority remained bystanders” (Phayer, 132). Susan Zuccotti describes Fascist-style Croats engaged in persecuting the Jews as “devout Catholics,” presumably ready to take orders from the pope if only he had been willing to issue the orders (Zuccotti, 113). Such views grossly exaggerate both the degree of the Catholic commitment of anybody actually prepared to persecute the Jews in this fashion–and the influence any pope or bishops could possibly have had on them, or in a Nazi-ruled Europe generally.

For in that time and place it must also be remembered that there were in force very severe penalties for opposing the actions of these totalitarian governments. There were thus a few other reasons besides the pope’s failure to speak out that may have persuaded people to be “bystanders.” As early as 1936, for example, priests in Germany were already being arrested simply for expressing sympathy for Jews and others in concentration camps.[xxxii] Even before the war, again, “ordinary Germans who were caught with hectographed copies” of Bishop Clemens von Galen’s sermons against the Nazi euthanasia program–a celebrated instance where a Churchman did strongly speak out–“or who discussed it with colleagues, were arrested and sent to concentration camps.”[xxxiii] Speaking generally, those who criticized Nazi action against the Jews “faced imprisonment”(emphasis added throughout).[xxxiv]

After the war began, “hostile civilians who…refused to obey a German order were denied any right, and, indeed, could be killed with impunity by German soldiers without resort to legal process…”[xxxv] During the attack on the Soviet Union, the German occupiers warned the Ukrainians: “Should anyone give shelter to a Jew or let him stay overnight, he as well as members of his household will be shot“(emphasis added again throughout).[xxxvi] Merely listening to Vatican radio was a criminal offense in wartime Germany (Rychlak, 149).

Under these circumstances, it is surely remarkable that anybody dared to do or say anything. Certainly it was not the responsibility of the Church or of any spiritual leaders to try to incite their followers to words or actions that would very often have resulted in nothing but a swift and sure martyrdom for them. The Church honors martyrdom but does not demand it of her members. On several occasions Pope Pius XII explained to various interlocutors that he was not speaking out because he did not want to make the situation worse. Most historians have tended to dismiss his words in this regard as an unconvincing excuse, but in view of the conditions that obtained in Nazi-occupied Europe for those who lived there, perhaps the pontiff understood better than his critics what the consequences of public challenges to the Nazis by him might have been. When historians and scholars a half century later write smugly about how Pius XII or the Catholic bishops should have done this, or should have said that, it is hard to credit that they really know what they are talking about, considering the conditions at the time. Yes, the Jews were being killed–but so was almost anybody who effectively tried to stand between them and their killers. Many did so anyway, of course, and heroically; but it was not something that a responsible moral leader could try to oblige them to do.

In short, the idea that Pope Pius XII should–or could!–have simply “spoken out” against the evils of Nazism runs up against some rather inconvenient realities–which some of the present-day writers on the Holocaust seem to have paid too little attention to.

III.

Five major questions need to be addressed and briefly answered before we go on to consider individually each of the ten books under review here:

1) Was Pope Pius XII, in fact, “silent” about the Nazi Holocaust against the Jews?

The basic charge of “silence” on the part of Pope Pius XII, of course, goes back to Rolf Hochhuth’s play The Deputy, but what too many may have failed to consider is whether there may not have been some very good reasons for what we may call the reticence, or the relative silence, with which the pontiff chose to conduct the Vatican’s public policy during the war.

In fact, the “silence” in question was only relative, for the pope did speak out, and often eloquently, in a traditional papal way in such documents as his first encyclical Summi Pontificatus, issued in October, 1939; in his annual Christmas messages broadcast during the war years; and in other addresses and allocutions to various groups, including the College of Cardinals. Many of these pronouncements of the pope received fairly wide publicity and diffusion at the time, given that they came from the pope. More than that, there were Vatican radio broadcasts and articles in the Vatican newspaper L’Osservatore Romano which had some impact (when the Fascists or the Nazis were not interfering with them).

The encyclical Summi Pontificatus, for example, addressed two major “errors” that were surely pertinent to the whole wartime situation: 1) The “law of human solidarity and charity which is dictated and imposed by our common origin and by the equality of the rational nature in all men, to whatever people they belong”; and 2) the divorce of civil authority from “every restraint of a Higher Law derived from God,” thus leading to the false worship of race and state.[xxxvii]

This encyclical certainly did attempt to deal with the problems then confronting the world in the way that the popes had traditionally dealt with such things, that is, by applying the Church’s teachings to them. One of the major problems with such statements in the minds of those susceptible to a Rolf Hochhuth kind of thinking, though, is that they are written in “Vaticanese”: they consist of broad and general statements couched in a rather mannered and elaborate style. In the view of papal critics, then and now, they fail to come to grips with a gigantic contemporary evils such as Nazism. Still, they cannot be equated with “silence.”

Nevertheless, if by “silence” is meant that Pope Pius XII did not denounce the Nazis and the Fascists by name, and did not, in particular, detail their manifold crimes, including those against the Jews, then it is true that the pope deliberately held back from following a course which he believed would have no effect and, worse, could incite the Nazis to further crimes and violence. This approach was not just something that Pius XII had decided on his own; it represented long-standing Vatican policy; it rested on the Church’s belief that in conflicts where Catholics are to be found on both sides, the head of the Church is obliged to be neutral.

Neutrality is especially important for the Vatican because in any war, it also sees its role primarily as that of a peace-maker. Pope Pius XII issued his five-point peace plan shortly after his election to the papacy, just as Pope Benedict XV had issued his five-point peace plan during World War I. This was one of the ways the popes believed it was appropriate to speak out. Pope Pius’s belief never wavered throughout the war that, as he said in his stirring address on the eve of the conflict: “Nothing is lost with peace; all may be lost with war.”[xxxviii]

Nor was there ever a time, before or during the war, when the pope did not hope to help mediate an armistice or peace settlement among the warring countries. In order to be able to play this role, however, the pope was convinced that he had to maintain a strict Vatican neutrality. If he did not denounce Nazi Germany directly and by name, then neither did he, for example, denounce Soviet Russia directly and by name. Yet while Catholic Poland was being swallowed up by Hitler, the eastern part of Poland and Catholic Lithuania as well were being swallowed up by Stalin. In the period 1939-41, according to the distinguished historian Norman Davies, “the Soviets…were killing and deporting considerably more people than the Nazis were…”[xxxix]

If Pius XII did not publicly and specifically condemn the Nazi death camps after learning about them, he also did not publicly and specifically condemn the allied bombing of cities. Though historians of the Holocaust rarely advert to it, the killing of the innocent in this way is as contrary to Catholic moral teaching as the killing of the innocent in the camps. Millions perished in the war, of course, just as millions perished in the camps; approximately 40,000 people were killed, for example, in a single allied bombing of Hamburg in July, 1943, no part of which was aimed at any military target.[xl]

In the midst of this generalized slaughter, since the pope disposed of no material means, and since the governments on all sides intent upon the pursuit of the war were more or less deaf to the entreaties he did from time to time make, the Vatican at least tried to do what it could do to ameliorate the situation. In this effort, diplomacy was the Vatican’s primary chosen means, not only in dealing with belligerent governments but also in attempting to help victims of the war, including Jews. Pius XII has been strongly criticized for preferring to use the means of diplomacy rather than plainly denouncing gross evil. Michael Phayer sees what he calls the pope’s “attempt to use a diplomatic remedy for a moral outrage” as Pope Pius XII’s “greatest failure” (Phayer, xii). Yet the pope was not following a policy that was original to himself; it was the traditional policy of the Vatican.

During World War I, for example, Pope Benedict XV did not condemn Germany by name in the case of German atrocities in Belgium. He was accordingly denounced by the allies for his “silence.” There was even a pamphlet published against him in 1916 entitled “The Silence of Benedict XV.”[xli]

Similarly, Benedict XV did not “speak out” against the twentieth century’s first notorious example of genocide–the massacre of over a million Armenians by the Turks in 1915. Rather, the pope made a strong diplomatic protest through his apostolic delegate in Istanbul; he also sent similar notes to the belligerent governments of Germany and Austria-Hungary, as well as to the Sultan of Turkey in Istanbul.[xlii]

Those who think that this consistent Vatican policy of strict neutrality in wartime was inadequate, considering the evils of the time, have a point; but they also need to remember the nature and the precariousness of the Vatican’s own position in the world. Following the conquest of the former papal states (1860), and of the city of Rome (1870), by the newly unified Kingdom of Italy, the Vatican had no international status; the popes were “prisoners in the Vatican,” entirely at the mercy of generally hostile Italian anti-clerical governments. Only with the conclusion of the Lateran Pacts in 1929, was the sovereignty of the Holy See over its minuscule Vatican territory recognized by an international treaty.

Article 24 of the Vatican Concordat with Italy (a component of the Lateran Pacts) declared Vatican City to be neutral and inviolable territory; at the same time, the Holy See had to promise to remain “extraneous to all temporal disputes between states.”[xliii]In other words, the Vatican was required to be strictly neutral by its own foundational document as an independent state. The policy was no mere whim or desire or personal policy of Pius XII, although he took it with the utmost seriousness and was determined to maintain it. The idea that he should somehow have abandoned Vatican neutrality in view of the special evil of the Nazi regime entails, of course, an acceptance of the further idea that solemn international covenants can be unilaterally abrogated at the option of one party–hardly an idea with which to oppose the lawlessness of Hitler. Moreover, abandonment by the Vatican of its own neutrality would have provided Hitler or Mussolini with a justification in international law for taking over the Vatican.

There were other reasons why Pius XII chose to follow the course that he did. He was pressured for his “silence” by both Axis and Allies, for example, from the earliest days of the war. More than once he stated (as we have already noted) that he was not speaking out in order not to make the situation worse for the victims. At one point, though, he did stretch Vatican neutrality to the limit by expressing his condolences to the rulers of just-invaded Belgium and the Netherlands; he was then promptly castigated by the Allies for not condemning Germany more explicitly, and by Germany and Italy for violating Vatican neutrality (this was one of the occasions when Mussolini had L’Osservatore Romano confiscated and its distributors beaten up).

In answer to a formal diplomatic protest lodged by the Italian Ambassador to the Vatican, the pope said:

The Italians are certainly well aware of the terrible things taking place in Poland. We might have an obligation to utter fiery words against such things; yet all that is holding Us back from doing so is the knowledge that if We should speak, we would simply worsen the predicament of these unfortunate people (Blet, 45).

Here the pope was not talking about possibly making things worse just for Jewish victims. At this point in time (May, 1940), it was Catholic Poles who were also being indiscriminately slaughtered in great numbers. As one historian later wrote: “…on the average, three thousand Poles died each day during the occupation [of Poland], half of them Christian Poles, half of them Jews…”[xliv]

The pope and his associates repeated on various occasions this same justification for not speaking out. In February, 1941, for example, the pope again commented that silence was “unhappily imposed on him” (Blet, 64). This was no mere excuse. At the Nuremberg Trials of Nazi war criminals after the war, Field Marshal Albert Kesselring testified that Pius XII no doubt did not protest “because he told himself quite rightly: ‘If I protest, Hitler will be driven to madness; not only will that not help the Jews, but we must expect that they will then be killed all the more” (Rychlak, 261).

Similarly, Dr. Marcus Melchoir, the Chief Rabbi of Denmark, who was himself rescued with his entire community by unpublicized efforts, expressed the same opinion after the war: “I believe it is an error to think that Pius XII could have had any influence whatever on the brain of a madman. If the pope had spoken out, Hitler would probably have massacred more than six million Jews and perhaps ten times the number of Catholics” (McInerny, 140).

The best known case of how publicly challenging the Nazis in occupied Europe could indeed make things worse, of course, is the case of the Dutch bishops. Their public protest, in July, 1942, against the persecutions being carried out by the Nazis resulted in the immediate revocation of what had been an exemption in favor of baptized Jews; and in the immediate deportation to Auschwitz and execution of all the Catholic Jewish converts, including the philosopher and Carmelite nun Edith Stein, later canonized by the Church. Jewish converts to Protestantism were not taken at this time because their leaders had agreed not to protest publicly.

All of our authors except David Kertzer record the Dutch incident (Blet, 147-148; Cornwell, 286-287; Marchione, 20 & 28; McInerny, 84-85; Phayer, 54-55; Wills, 54-56; and Zuccotti, 312-313); José Sánchez touches on it only fleetingly, but seems to accept that the public protest of the Dutch bishops “led directly to the deportation and killing of Jews who had converted to Catholicism” (Sánchez, 133).

The anti-Pius authors are not so sure. John Cornwell accepts the basic facts but then launches into a discussion of how the incident has been used as the basis of “exculpatory statements” for Pius XII; he particularly objects to one by the pope’s long-time housekeeper, Sister M. Pasqualina Lehnert, who, many years later, reported that the pope had actually proceeded to destroy a protest document he had drafted against the Nazi persecutions when he learned of this incident concerning the Dutch bishops.

Michael Phayer is even more skeptical than Cornwell about this story, using the incident to question the credibility of Sister Pasqualina. Garry Wills cites the story in order to question the legitimacy of the canonization of Edith Stein as, properly speaking, a Catholic martyr (and not just another Jewish victim). Susan Zuccotti cites the story mostly as related to her primary subject, the Holocaust in Italy, but finally concedes that “the pope was probably correct that some Jews involved with Catholicism, as well as some Catholics, would suffer from a public protest”–she does not concede that a papal protest might have made things worse for the Jews as such, since her primary thesis is that many more Jews suffered and were sacrificed than necessary because the pope never found a way to speak out against the Nazis.

The pro-Pius authors take the opposite viewpoint; they are all convinced that the incident strongly vindicates the Vatican’s policy. Pierre Blet records that the Vatican had actually been expecting a much better outcome in Holland based on diplomatic reports it had received; and was surprised and dismayed by the deportations (which would seem to indicate that the Nazis did change their policy abruptly). Margherita Marchione strongly deplores the protests later raised against the Church’s beatification of Edith Stein as a result of her deportation and death. Ralph McInerny speaks of the “the tragic consequences of open confrontation” and reports the actual words of the Nazi Reichskommissar reacting to the public protest of the Dutch bishops: “If the Catholic clergy does not bother to negotiate with us, we are compelled to consider all Catholics of Jewish blood as our worst enemies, and must consequently deport them to the East.” Ronald Rychlak points out that the Reichskommissar in question expressly stated that the Catholic bishops had “interfered,” and therefore the deportations had to be carried out.

The particular interpretation of each of our various authors of this particular incident is typical of their treatment of Pius XII and the Holocaust generally: the same set of facts is made to serve each author’s position, whether for or against the pope.

Still, nothing related to this incident suggests that there were not serious consequences or penalties for speaking out against the Nazis or trying to pressure them. On the contrary, it seems that even the anti-Pius authors basically have to concede this in this case–while, in the case of a couple of them, fuzzing the whole thing up by then diverting attention to the credibility or lack of it of Sister Pasqualina.

Other examples of the same kind can be cited, however. In Hungary in 1944, for example, in a liberated Rome when Pius XII and his nuncios were in a better position to speak and act more forcibly and were quite vigorously doing so–and with some success in preventing further deportations of Jews–the Germans responded by overthrowing the Hungarian government and installing a new and more violent one willing to proceed against the Jews.[xlv] That resistance to the Nazis often did make things more difficult for the victims was an established pattern in Nazi-occupied Europe. Pius XII was not merely rationalizing his decision not to speak out forcefully by saying it made things worse; he was referring to a reality that was obvious to those coping at the time with the war and the evils it had brought in its train.

And there were yet other reasons for the course of action which Pius XII followed. No better summary of them probably exists than that of J. Derek Holmes in his book The Papacy in the Modern World:

[Pius XII] was very skeptical, probably rightly, about the influence of public denunciations on totalitarian regimes. Such condemnations were not only useless, but might even provoke retaliation.

Pius XII was certainly concerned to safeguard German Catholicism from the threat of National Socialism and might even have been afraid of losing the loyalty of German Catholics. He was also anxious to avoid jeopardizing the position of Catholics in Germany and in the occupied territories. Judging from the pope’s correspondence with the German bishops, fears of reprisals would seem to have dominated his attitude towards the fate of the Jews in Germany. The very evil to be condemned was sufficiently evil to be able to prevent its condemnation. But the pope had to struggle hard to maintain his “neutrality.” He was certainly well-informed and there is a suggestion of total helplessness in his letters in the face of such incredible evil. Even if he made the wrong decision in keeping “silent,” he cannot be accused of taking the decision lightly. Finally, the pope’s own work on behalf of the Jews might have been endangered by a public denunciation of the Nazis, even though such a denunciation might have justified his moral reputation in the eyes of mankind.[xlvi]

These, then, were some of the reasons why Pius XII decided upon the relative silence he maintained in the face of the Holocaust. He was far from totally silent, as we have seen, even as through the organs of the Church he worked to help the Jews and other victims.

As for the effect of some of the statements that he did make during the war years, one researcher, Stephen M. DiGiovanni, had the idea of going directly to the New York Times, available on microfilm in most large libraries, to see what America’s newspaper of record had to say about Pius XII as events in wartime Europe unfolded. The results of his inquiry, available on the website of the Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights,[xlvii] cast considerable doubt on the allegations, still being repeated more than a half century later, that Pius’s statements were too few, too muted, and too indirect ever to enable the public understand what was happening in Europe under the Nazis.

It is true that many historians sniff at mere newspaper article research, preferring no doubt to burrow in the archives. Still, it is hard to credit the overall thesis of the pope’s culpable silence when we come upon such New York Times headlines as these: POPE CONDEMNS DICTATORS, TREATY VIOLATORS, RACISM (October 28, 1939); or, POPE IS EMPHATIC ABOUT JUST PEACE…JEWS’ RIGHTS DEFENDED (March 14, 1940); or when we come upon Times editorials such as those commenting on the pontiff’s 1941 and 1942 Christmas Messages where the pope is described as “a lonely voice crying out of the silence of a continent.”

2) What did Pius XII do for the Jews and could he possibly have done more?

It is surely something of a truism to say that historical figures could have “done more” or acted differently, but it is also beside the point. The proper task of history, it would seem, is to understand what someone did and why. When a Pius XII is instead charged with “silence,” it is very hard to deal with the question; it is like an unprovable negative.

Actually, Pius XII and the Vatican were heavily involved in relief work throughout the war, quite apart from what the pope said, or did not say; on the “silence” question, Margherita Marchione, among other authors, points out that other agencies involved in relief work were similarly “silent.” She notes that the World Council of Churches, for example, left any possible denunciations of crimes to its member churches–just as the Holy See regularly left it to the Catholic bishops to say whatever seemed necessary or helpful.

Similarly, the International Red Cross, according to Marchione, began drafting a protest statement against the Nazis in 1942. It was never issued, however (Marchione, 174-175). In February, 1943, at a meeting called to examine the problem of helping Jews threatened by the Nazis–a meeting which included the papal nuncio as well as a pastor from the World Council of Churches–the Red Cross articulated its reasons for deciding not to issue any protest statement; protests, in the view of the Red Cross, would jeopardize the relief work the agency was carrying out in favor of war victims:

Such protests gain nothing; furthermore, they can greatly harm those whom they intend to aid. Finally, the primary concern of the International [Red Cross] Committee should be for those for whom it was established (Blet, 162).

That this was the considered view of the Red Cross reveals a great deal about how the situation was viewed at the time. Yet I do not recall that a single one of the anti-Pius books–nor do the indexes of any of them reveal–any mention of the fact that the Red Cross, like the Vatican, was attempting to carry on doing what it could do in the way of relief without issuing direct challenges to regimes which exercised iron control in the very territories where most of the victims in need of assistance were located. José Sánchez does mention this “silence” of the Red Cross, but goes on to say that, in his view, more was expected of the pope as “the moral voice of Catholicism” (Sánchez, 120).

In this connection, people have often asked why Pius XII did not excommunicate Hitler, a baptized Catholic, along with those Catholics who participated in the Nazi killings. Our authors generally do not dwell on this question, perhaps considering themselves to be at a level of sophistication above asking such a question. Certainly any such excommunications would have constituted a provocation, if that was what the pope, like the Red Cross, was trying to avoid.

More than that, though, while excommunication might have been effective back in the ages of faith, when a head of state had to contend with strong feelings about excommunication on the part of his subjects, in today’s secularized world it was not likely to have much effect. The Holy See, moreover, had first-hand experience of how ineffective excommunications had been for a very long time: the excommunication of Queen Elizabeth I had certainly not helped the Church in England; nor did it deter Napoleon. In more recent times, the pope had without any discernible effect whatsoever excommunicated the Savoy ruler who became King Vittorio Emmanuele I of a United Italy, along with his famous Prime Minister Count Camillo Cavour. The excommunications of both of these men then simply had to be quietly lifted to enable them to receive the last Sacraments of the Church at the time of their deaths.[xlviii]

More than that, Hitler had long since “excommunicated” himself; he had not practiced the Catholic faith since childhood, and on numerous occasions had expressed his hatred of it (Rychlak, 272-273). Nor does it seem that those who proved themselves capable of engaging in the Nazi killings could have been much influenced by being told that they had been excommunicated. Excommunication would have amounted to an ineffective gesture (like speaking out). More important for the pope would be what could effectively be done under the circumstances.

So what did the Vatican do for war victims, including the Jews? Pope Pius XII set up both a Pontifical Relief Commission and a Vatican Information Service; the former was designed to provide aid in the form of whatever funds, goods, medicine, or shelter could be obtained and distributed, while the latter aimed to find and report on missing soldiers or civilians who had become separated because of the war. Headquartered at the Vatican, these organizations raised money, for example, in the Americas, and then worked through Church institutions and personnel at all levels to funnel aid to needy victims. Thousands of people were involved in this work: priests, monks, friars, nuns, lay volunteers, military chaplains, and others. The networks established by and through these organizations would also prove to be instrumental in hiding Jews or helping them to escape.

From the outset Pope Pius insisted: “It is our ardent wish to offer to the unfortunate and innocent victims every possible spiritual and material succor–with no questions asked, no discrimination, and no strings attached.”[xlix]

In other words, the assistance specifically provided by the pope and the Church to the Jews was rendered to them along with the aid provided to other wartime victims, It was the Church’s policy, as well as the Church’s boast, that whatever assistance she could give would be given impartially. Ralph McInerny observes that because the Church was engaged in defense of the “the common rights of the innocent, there was no need to make special mention of the Jews. The Church must come to their defense as to that of any other innocent victims”–he also notes, though, that “Pius XII did make special mention of the Jews” anyway (McInerny, 59).

Since so much is commonly made about what Pius XII did not do for the Jews, there is obviously a great misunderstanding at work here. While the Church saw herself as attempting to provide help indiscriminately to all, including the Jews, most of the anti-Pius writers see the pope’s “failure” to single out the Jews for mention more often and more specifically than he did as proof of his alleged small concern for the Jews and their unique problems, if not as actual anti-Semitism on his part (Cornwell, 296-297; Phayer, 41 & 110; Wills, 66-67; Zuccotti 1-2 and passim). David Kertzer even declares that “as millions of Jews were being murdered, Pius XII could never bring himself to publicly utter the word ‘Jew'” (Kertzer, 16).

Kertzer, of course, is mistaken about this, but his very exaggeration indicates the depth of the emotion invested in this question by some of our authors. This raises a further question, though, of why the anti-Pius authors generally give so little attention to the actual wartime and relief and rescue efforts that the Church did carry out, however inadequate they may have been in comparison with the enormity of the Holocaust against the Jews. These efforts are pretty consistently downplayed or even ignored by most of the anti-Pius authors, even while they go on at length about the inaction of Pius XII and his supposed negative attitudes towards the Jews.

On the other hand, all of the pro-Pius authors strongly emphasize the Church’s wartime relief efforts. All of them quote the estimate of Israeli diplomat and pro-Pius author Pinchas Lapide that “the Catholic Church, under the pontificate of Pius XII, was instrumental in saving at least 700,000, but probably as many as 860,000 Jews from certain death at Nazi hands” (Blet, 286; Marchione, 2 & 50; McInerny, 168-169; Rychlak, 240 & 404).

José Sánchez also quotes the same passage but then calls it “undocumented” and says the “uncritical acceptance of Lapide’s statistics and statements has weakened [the] arguments” of the pope’s defenders (Sánchez, 140). Yet Sánchez himself has little more to say at all about what the pope and the Church did, in fact, do in a positive way to help the Jews; and, in this respect, his book resembles the books of the anti-Pius authors.

The anti-Pius authors themselves, however, with the exception of Susan Zuccotti, ignore Lapide’s statistics completely, not merely as inaccurate, but as if they did not even exist. Relying on the these authors alone, it would be hard learn that Pius XII did anything or helped anybody, and this represents a serious failure on the part of these authors to deal with all the facts of the case.